This week I’m sharing my own experience with a studio visit from another artist. As readers of Vasari21 may remember, I spent a few years trying to turn myself into an artist before finally giving up because I just never developed the vision thing, and I’ve looked at enough art to know I just don’t have the right stuff. But I will say that in those few years I learned a lot about the difficulties of making art and the frustrations of real artists, so I don’t consider it wasted effort, an I got a few passably good paintings out of the whole experience.

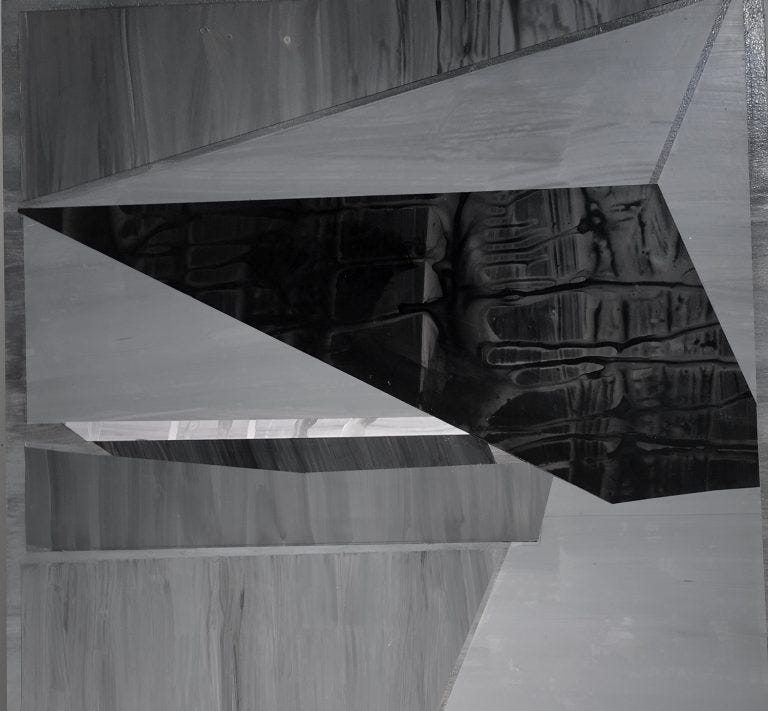

After about a year of concerted endeavors and experiments with a material called Dura-Lar, I found myself going in about three or four different directions. I wanted some advice on what seemed the most promising, and so I turned to an artist friend here in Taos whose judgment I was reasonably sure I could trust.

Oh, how little we know people until we ask for an opinion!

Katrina, as I’ll call her, swept into the studio on a chilly late afternoon a few years ago. She did not spend much time looking around before launching into a full-scale attack. She honed in on a group of four foot-square panels and turned them face down, all but one, on the shelf that supported them. “Oh, I don’t like these at all,” she said. She barely glanced at some geometric works that I’d lately started and focused instead on some landscape-y things made the previous summer, which I’d begun to think were rather corny.

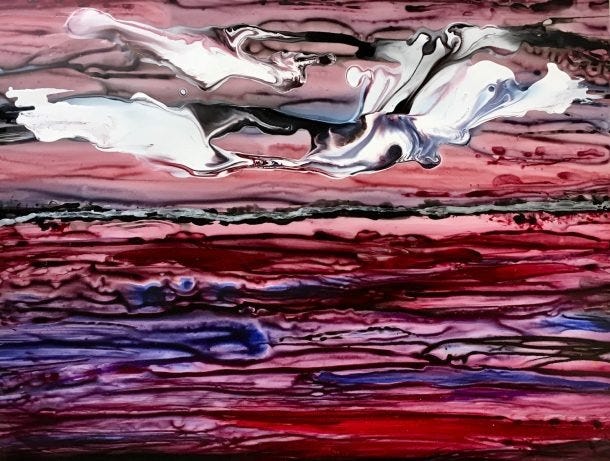

“These are just awful,” she pronounced about some abstractions that to me had a certain appealing Asian inflection (they now hang in my ex-husband’s house and look quite terrific…at least he and his next-door neighbor love them). “But these are rather nice,” she said of the groups of small panels (about three- and four-inches square) I called “Sky Boxes.” I think they’re pretty, too, but I came full-stop to a dead end and couldn’t make anymore.

“You need to mix your colors. How are you mixing your colors?” Katrina demanded. I showed her my ceramic palette with small wells for mixing the high-flow acrylics I use. “Oh, this is not right. You need to lay out your colors on a real palette.” Even though I explained that the runny paints do not lend themselves well to traditional ways of blending one color with another, she needed to see for herself and squirted out a few drops of different shades on a sheet of Dura-Lar. She used a brush to try to mix the paints, but they quickly started to dry out and you can’t really squeeze out enough paint on a flat “palette” to cover even a small surface.

After about 45 minutes of full-frontal assault, I was stunned, dazed, and confused. “Have you ever taught?” I asked her.

She looked startled and breathed in sharply. “Yes, I’ve taught at RISD and Parsons and a few other places.”

“Were you this rough on your students? Don’t you think a gentler approach would work better?”

There was no answer, but at that point I just wanted to hustle us off to the dinner we’d planned with a friend.

I couldn’t go back into the studio for a few days. And indeed I never wanted to talk to Katrina again. She later apologized, via email, explaining that she’d almost driven into a guard rail on her way over and was feeling tense and on edge. But I don’t find that sufficient excuse for what was almost bullying and disrespectful behavior.

The takeaway value of the visit for me was nil. But I did realize that if I ever do this again—and I probably won’t—I would set up the work differently, group the various separate efforts together—instead of scattered about, as I had them—and ask very pointed questions. “Which of these appeals to you most?” “Which seem most promising?” “And how the hell do I find something I want to stick with for more than a few months?”

When I posted about the visit on Facebook, there was a flurry of sympathetic responses. One member of the site emailed me, saying, “Your artist friend did not give a comprehensive critique because she didn’t ask you the right questions. Good crits come with multiple views.” Others told of similarly brutal visits from art dealers or ugly attacks in art school, long distances traveled to have “experts” look at work, only to get a thumbs-down. The life of an artist, I have learned, contains more slings and arrows than acting auditions for an off-off-Broadway play.

You read my post last week about how to conduct a studio visit. But perhaps there needs to be some sensitivity training for the other side as well. Artists, even amateurs like myself, are delicate creatures, no matter how tough the shell we try to cultivate. When asked to give some guidance and feedback, it’s not really enough to say “Oh, I like these!” or “I hate these!” without offering some explanation as to why the works succeed or fail. When I’ve done studio visits myself, I’ve been careful not to handle things without permission. I try to give a fair and articulate opinion. I would never, ever say, “This is really tired stuff” or “I can’t stand these.” That’s not helpful to the artist and reflects poorly on the visitor.

The rules of studio visits should be fairly simple. Above all, especially if you’re an artist yourself, simply abide by the Golden Rule: “Do unto others….”

You know the rest.

Hello Ann - So nice to be reading you again.

I have learned that perservering as an artist has meant learning to take the "bad" times, the blundering critics, the endless rejections and, worst of all (for me) an acute sense of invisibility. The rebound gets shorter and quicker and the sense of self stronger and unmoveable . . . and there is the work . . .

I taught painting and drawing for years at a community college and many of my students were very vulnerable. My own rules for critics was to first say 3 positive comments followed by constructive suggestions. Most of my students were not going to go forward as art majors but I wanted them to love art. Research projects always included 50% women!