A couple of unrelated cultural happenings got me thinking about the nature of portraiture this week. One was Amy Sherald’s highly praised mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York. The other is the haunting story of the wily courtier Thomas Cromwell and his ruthless employer, Henry VIII, in the series “Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light.” The former because Sherald’s pictures are billed as outstanding portraits of Black Americans; the latter because the subjects and the eerily tenebrous lighting of the show recalled for me the extraordinary portraits of the Tudors and their circle by Hans Holbein the Younger. (It’s fortuitous that Holbein’s paintings are stars of the recently re-opened Frick Collection, which also boasts several other knockouts of the genre, like Ingres’ Comtesse d'Haussonville and Titian’s Man in a Red Cap.)

No matter how much hoopla has surrounded the show, I don’t think Sherald’s paintings succeed as portraits. “Roaming the galleries…, I thought of writers like Toni Morrison and Zora Neale Hurston, and their poetic yet unflinching refusal to look away from the everyday horrors of American life,” claims Hyperallergic’s critic Jasmine Weber. Huh? What horrors are here? Granted, I can only survey the show in online reproductions, but I don’t see anything too horrible. Her subjects either float against monochrome backgrounds, as in the likenesses of Michelle Obama and Breonna Taylor, or they pose with a bicycle against a white picket fence, frolic at the beach on a perfect summer’s day, or sit aside a John Deere tractor that’s never known a speck of mud. They are dressed in pretty, stylish outfits with cute props: one holds a bunny, for example, another a gigantic teacup. They are graphically ingratiating and could serve as striking magazine covers (indeed Ms. Teacup, aka Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance), from 2014, recently introduced the March 17 issue of The New Yorker.

By contrast, let’s look at Holbein’s 1540 portrait of Henry VIII, painted in the monarch’s 50th year. He is majestic, he is commanding, he threatens to burst the confines of the frame, and the amount of glitz he carries on his person could sink a Spanish galleon. But Holbein also gives him a shrewd and calculating gaze as skillfully as he endows Thomas More with a steadfast, resolute demeanor, or Cromwell himself with a rather piggy wariness. Which is not to say that a great portrait really needs to tell us something about the subject. Indeed great portraits are sometimes vanity projects: Do we really believe the pint-sized hero of Waterloo was as dashing as artists like Gros and Delacroix depicted him? Are these any the less “successful” as painted likenesses?

In his recent review of Don Bachardy’s portrait drawings at the Huntington in San Marino, CA, critic Christopher Knight notes, “There’s a habit of claiming that a portrait means to ‘capture an essence’ or ‘reveal interiority’ concealed within the subject, but I’m skeptical of such assertions. Portraiture is instead all about recording a surface — as fully, robustly and truthfully as possible — which, if successful, will allow for the unencumbered experience of the sheet of marked paper set before a viewer’s eyes.”

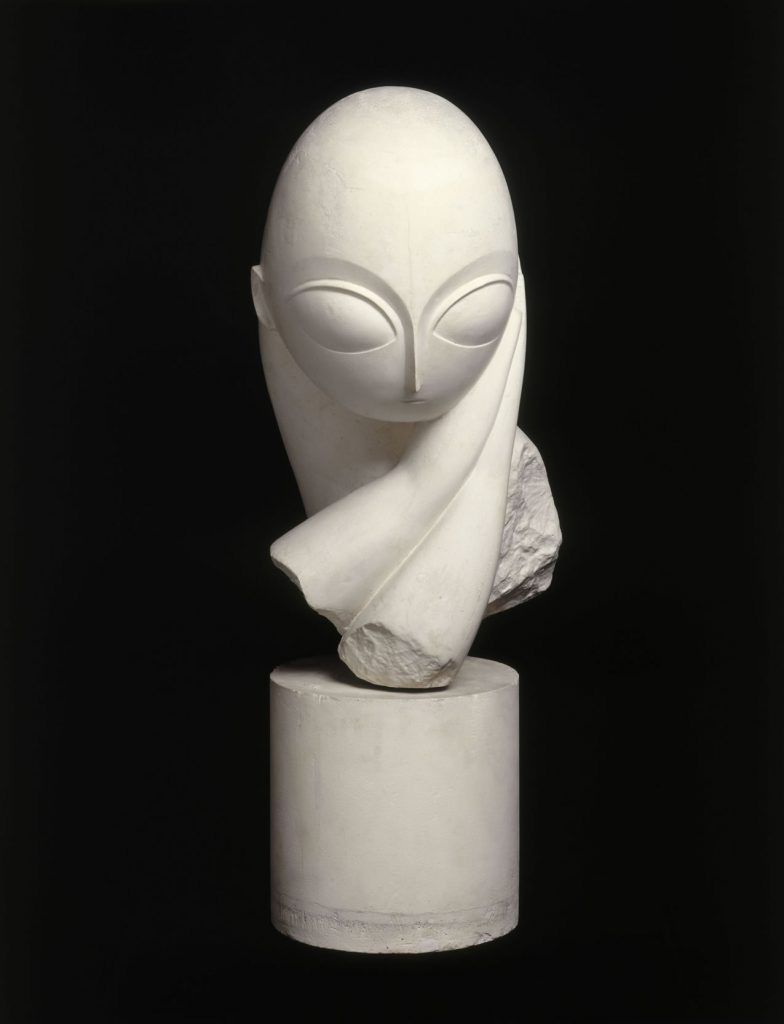

I don’t entirely disagree with that—it encompasses the realist as well as the expressionist artist—but it also leaves out a whole lot of art history, like the encaustic Fayum mummy portraits of Roman Egypt and all likenesses carved in stone or made from other three-dimensional mediums. The Romans were famed for their portrait busts, as were Bernini and Houdon, and what of Daniel Chester French, who made the monumental statue of Lincoln that graces his memorial in Washington, DC? All of these are about more than recording a surface, “robustly and truthfully.” Indeed, surface is the least of it. Many monuments in stone nearly breathe with an inner force, like Bernini’s portrait of his mistress, Costanza Boranelli, who seems on the verge of blurting some closely guarded secret.*

As noted, some portraits are clearly beautiful lies, like any number of society divas captured by Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds (though we can never know for sure how many cosmetic liberties were taken because we certainly don’t have photographic evidence to compare them with).

And when we arrive at portraiture in the early 20th century, all manner of madness breaks loose. Brancusi’s many versions of Mademoiselle Pogany reduce a young art student to a bug-eyed ovoid resting her cheek atop vestigial hands; Juan Gris explodes his friend Picasso into jagged Cubist shards; and Marcel Duchamp plays with gender-bending in his self-portraits as Rrose Sélavy. But by and large, throughout the last century, portraiture remained the province of traditionalists and a few brave individuals like Alice Neel, who pushed the expressive possibilities about as far as they can go while still remaining part of the hallowed practice of the artist training her vision on her subject (and sometimes vice versa, as when James Lord documented his sessions with Giacometti in A Giacometti Portrait).

Which leads me to note that Amy Sherald largely works from photographs and perhaps that accounts for a certain lack of affect, even if it’s standard practice for many contemporary portraitists.

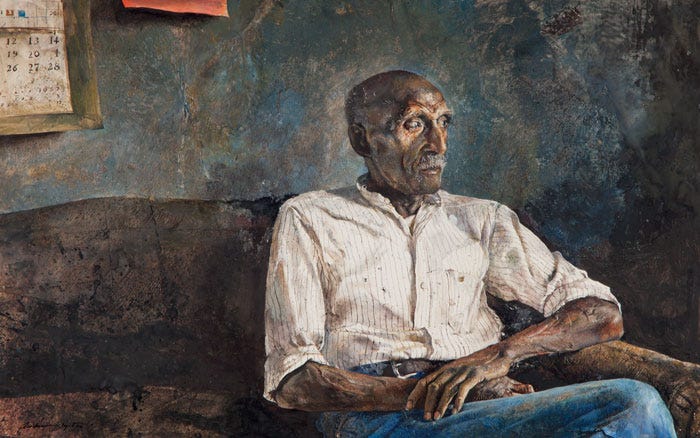

Extravagant claims have been made for this show, including that Sherald has injected the genre with new life. That same critic for ARTnews opined: “overall [the portraits] reflect the built-in challenges of making work that functions as celebration, critique, and revision of American visual culture all at once.” And that’s some heavy lifting, for sure. Hyperallergic’s reviewer and one of the show’s curators maintain that Sherald follows “in the tradition of Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper” (huh? since when was Hopper known for his portraits?). Well, have a look at Wyeth, have a look at Sherald, and you tell me who makes the more compelling paintings.

*Alas, poor Costanza. Bernini was having an affair with her when he discovered she was dallying with his brother as well. The sculptor smashed his brother’s ribs and sent a servant to slash Costanza’s face with a razor, a traditional punishment for a woman who had offended a man's honor.

Well perhaps they look better in the "flesh" but how in the world can these pictures (maybe they are paintings) compare with the masters? I see more in Hockney's portraits than with this mid career artist. Her work looks undynamic, flat, and a watered down version of what is beautiful.

And of course there is more smacking of DEI. A painter's painter? I don't buy it. Wisdom (huh?)

Thanks Ann, this is a good one. I'm responding to a responder. I yearn for the Frick

Ann, thank you for this. I often wonder if I am the only person who is not agog over Amy Sherald’s portraits. (It’s good to know I have you for company). Ever since I first saw her portrait of Michelle Obama at SAAM in 2018 - and then attended her 2019 solo at Pace, when I really tried to be open-minded and to give Sherald another chance - I have found little to admire. (I prefer Kerry James Marshall’s figurative work any day). Sherald sits at the top of my ‘overrated artists’ list.