Alarmed at the temper of the times, I’m forgoing my usual recycling and/or refurbishing of a Vasari21 post and trying to sum up what we can expect, so far, from the Trump-Musk administration (even as J.D. Vance is cozying up to the neo-Nazis in Germany). This week, let’s take a look at history. Next week, I’ll try to bring you more concrete observations and predictions from the frontlines.

Among the executive orders issued by Donald J. Trump in his first weeks in office, one in particular flipped a switch in my brain. The decree, called “Promoting Beautiful Federal Public Architecture,” states that “federal public buildings should be visually identifiable as civic buildings and respect regional, traditional, and classical architectural heritage in order to uplift and beautify public spaces.” It goes on to explain that heads of US government departments, presumably with architectural plans in the works, must submit recommendations to advance this policy within 60 days.

When Trump issued a similar order in his first term, architects were immediately up in arms: Reinhold Martin, an architecture professor at Columbia University, told The New York Times in 2020, “This is an effort to use culture to send coded messages about white supremacy and political hegemony.” More recently, another architecture critic, Kate Reed of The Nation, expanded on the January 2025 mandate: “It doesn’t matter to Trump et al. that actually building in a traditional style is astronomically more expensive and wasteful, or that adding another layer of bureaucracy to aesthetic production smacks of Albert Speer–style despotism.”

Does this remind anyone of the history of art and architecture in Nazi Germany? Says Wikipedia: “Upon becoming dictator in 1933, Adolf Hitler gave his personal artistic preference the force of law to a degree rarely known before. In the case of Germany, the model was to be classical Greek and Roman art, seen by Hitler as an art whose exterior form embodied an inner racial ideal. It was, furthermore, to be comprehensible to the average man.”

Before Hitler came to power in 1933, the arts in Germany saw an extraordinary explosion of creativity and experimentation during the so-called Weimar Republic. There was a Berlin Dada group, whose members included Hannah Höch and George Grosz. A Cologne offshoot of Dada was founded by Max Ernst and Jean Arp (in one of their exhibitions, a work by Ernst featured an axe "placed there for the convenience of anyone who wanted to attack the work”—which sounds like a bit of a precursor to certain Happenings and performance pieces.

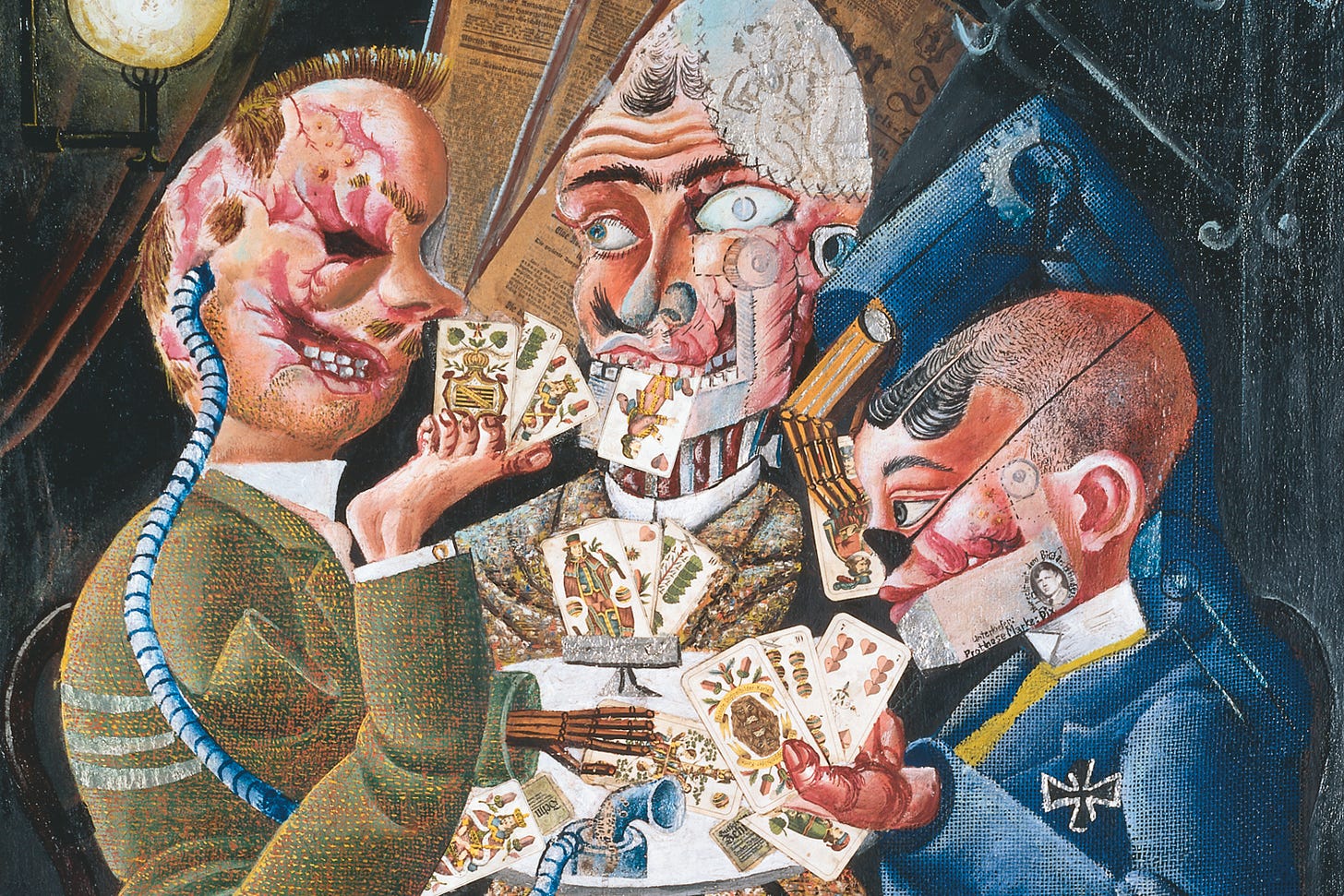

A movement known as the New Objectivity (in German the Neue Sachlichkeit) gained traction as a reaction to the emotive and spiritual aspirations of Expressionist artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Alexei Jawlensky, still very much alive and working. Georg Grosz and Otto Dix championed an art that was "raw, provocative, and harshly satirical,” per our good friend Wikipedia.

And the Bauhaus—home to Klee, Kandinsky, Gropius, and others in search of a unified aesthetic—remained a force until the Nazis forced its closure in 1933.

All of this intellectual and creative ferment did not immediately grind to a halt, but the wiser and more intrepid spirits saw which way the wind was blowing and decamped for the U.S., Great Britain, and elsewhere. After Hitler was named chancellor, Nazi agents scoured the museums that had collected the leading lights of the avant-garde in France and the Weimar era and removed more than 20,000 artworks from state-owned museums. In 1937, 740 modern works were exhibited in the defamatory show Degenerate Art in Munich to “educate” the public on the “art of decay.” “The exhibition purported to demonstrate that modernist tendencies, such as abstraction, are the result of genetic inferiority and society’s moral decline. An explicit parallel, for example, was drawn between modernism and mental illness,” says the website for New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which has some fine examples from the show online. Degenerate art, in Hitler’s lexicon, was “an act of aesthetic violence by the Jews against the German spirit,” wrote historian Henry Grosshans in his book Hitler and the Artist, even though most of those in the show were not even Jewish. (You can also get a little tour of the “degenerate” show in opening sequences of the film Never Look Away (loosely based on the life of Gerhard Richter), which strike me as quite convincing from what I’ve been reading.)

A second exhibition, held at the same time as the “Degenerate” art show, made its premier at the palatial Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German art) amid much pomp and fanfare and featured officially approved artists such as Arno Breker and Adolf Wissel. "The audience entered the portals of the new museum…to a stultifying display carefully limited to idealized German peasant families, commercial art nudes, and heroic war scenes,” says Wiki. “The show was essentially a flop and attendance was low. Sales were even worse and Hitler ended up buying most of the works for the government.” At the end of four months, the show of “degenerates” had attracted over two million visitors, nearly three and a half times the number that visited the officially sanctioned show.

And what, in the realm of aesthetics, did Hitler and his minions admire? According to historian Klaus Fischer, "Nazi art…was colossal, impersonal, and stereotypical. People were shorn of all individuality and became mere emblems expressive of assumed eternal truths. In looking at Nazi architecture, art, or painting one quickly gains the feeling that the faces, shapes, and colors all serve a propagandistic purpose; they are all the same stylized statements of Nazi virtues—power, strength, solidity, Nordic beauty."

More alarming for our times, it seems to me, was the establishment of a Reich Culture Chamber in 1933, with Joseph Goebbels as its Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Within a few years there were 100,000 members, whose purpose it was to oversee the press, radio, literature, movies, theater, music, and visual arts, prohibiting for example atonal music, blues, jazz, and any visual arts that did not reflect the rampant quest for Aryan norms.

Could anything similar happen here? If Donald Trump can make himself chair of the Kennedy Center in Washington (I shudder to imagine what kind of programming he has in store) and dictate terms to architects of federal buildings, one wonders what’s next. Make no mistake that this is a man who is very conscious of the power of images. As a New York Times report on Friday noted, there is “a pronounced trend in how he and his allies are using imagery with an almost imperial aesthetic to project an air of ubiquity, authority and invincibility.”

Sieg Heil!

If this is all too depressing to contemplate, spend some quality time with Pieter Bruegel the Elder in this exercise from the Times. The analyses at the end are fascinating.

Such a timely and eye-opening piece, Ann. But we can't lose hope. If Democrats want to win in the midterms, they need to speak in concrete terms that masses understand (many don't really know what terms like fascism, hegemony or even democracy mean.) rather than abstractions. Talking about salaries, groceries, hospital costs, freedom to choose, and the like will help us in the mid-terms.

Excellent Post Ann. Thank You