Though I haven’t attended in person in more than two decades, I always like to check in on what’s new and “hot” at Art Basel Miami Beach, an international extravaganza featuring works from 250 galleries. And every December, I find myself hopelessly out of it, occasionally charmed but mostly bewildered by the selections displayed online.

Much earlier in the year, I was dismayed to read of the cancellation of an exhibition focused on the legacy of art historian Michael Fried’s landmark 1965 show, “Three American Painters,” months before its opening. The show would have highlighted works by a number of artists who were “hot” when I was in my late teens and early 20s and just beginning to get seriously interested in art. They included Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland, and Frank Stella and 22 other artists, among them Anthony Caro and Helen Frankenthaler. No clearcut reason was given for bumping the show from the docket other than the new director of the museum in question thought the artists would not appeal to a “diverse community.”

All this made me wonder if we art writers sometimes get stuck in a bit of a time warp, still enthralled with the artists who first turned us on. And so I recalled this essay, published nearly nine years ago, which still seems to resonate, especially when I read of the show dedicated to Helen Frankenthaler now at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence.

My first boyfriend, in college, always smelled of Ivory soap. It was a clean, innocent scent, like baby powder or shampoo, and therefore perhaps appropriate for young love. For years after we broke up, whenever I smelled Ivory soap on another person, male or female, I would be filled with nostalgia and longing.

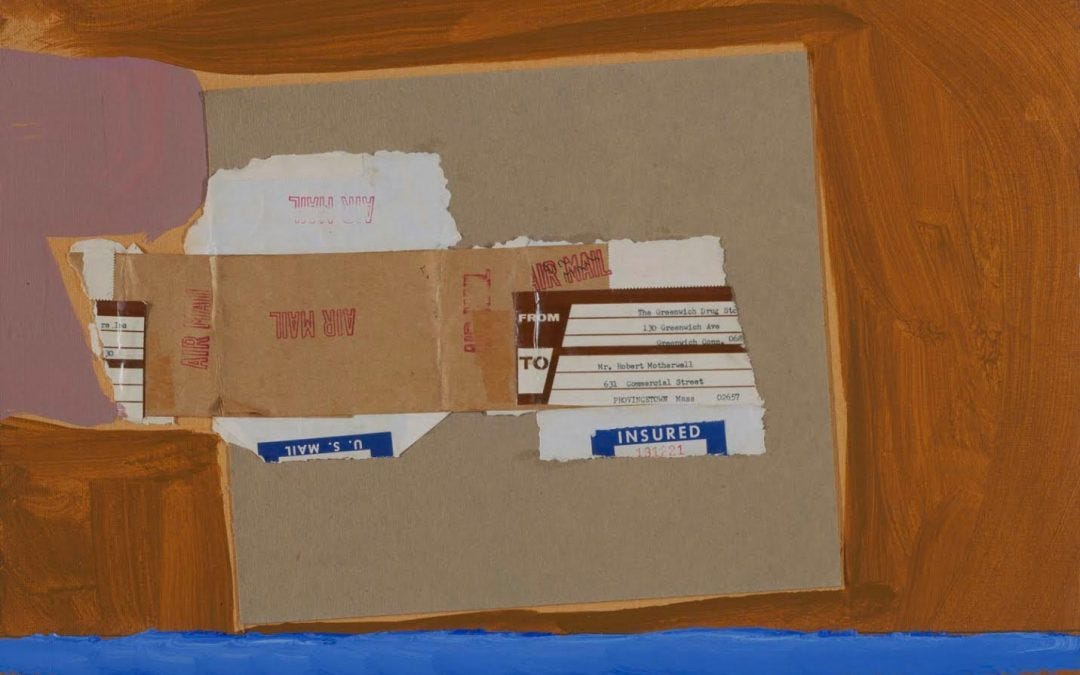

But this is not a story about romance. It’s about art, and a similar phenomenon I believe happens with certain works of art. Late one night, I flipped over the current issue of New York Review of Books and there was a Robert Motherwell collage, The Irregular Heart, as part of an advertisement for a show at Paul Kasmin Gallery. My own heart was feeling a little irregular too, doing something like the thumpa thumpa drumbeat accompaniment to love at any age.

When I was in college, around the time of that first beau, I fell madly in love with Helen Frankenthaler, and by extension, Motherwell, her husband from 1958 to 1971. I would pore over reproductions of the paintings, prints, collages of both. I was briefly a studio-arts major at Princeton, but the university in those days was no place for a budding artist, though I believe the school was trying its best with only two or three people on the art faculty. The work I was doing, though, was nothing like Frankenthaler’s or Motherwell’s. To the best of my recollection, my canvases were subdued geometric things in pale washed-out colors, mostly beige and gray. My adviser was Michael Graves—not yet the Michael Graves—who would come to my studio, spout a little Noam Chomsky for reasons still unclear to me, and then explain that if I had a vertical element there I needed a horizontal element here.

It all felt strangely inauthentic, and after a year of struggling in the studio, even after winning some kind of prize for my canvases, I switched over to an art-history major and wrote my junior paper on—who else?—Helen Frankenthaler. If I couldn’t be Helen, I could at least write about her work. And I believe I see something of her in The Irregular Heart in the bands of “off” colors at top and bottom—remove the torn air-mail stamps and prosaic brown-paper packaging and you might indeed have a Frankenthaler painting, though probably not a very good one.

I can in part explain how this collage works formally—a very clever move to smack that address label, with its no-nonsense stamps and typescript and whiff of bohemian glamor (Provincetown!), on top of the lyrical rush of paint. But I can’t fully explain my emotional reaction, unless it has to do with a powerful kind of love and nostalgia.

I do know, though, that artists and art lovers have extreme responses to certain works of art. My friend Christine Taylor Patten, whose drawings were part of our last show at the Wright Contemporary, recalls being in the Galleria Borghese in Rome when she was eleven years old, while her family was living in Europe. “I went to the Borghese with my parents and got separated from them when they went into another gallery,” she recalls.” I was alone in the large sculpture gallery, wholly mesmerized by the beauty and strength of all the huge sculptures and couldn’t resist going around from one to another, feeling the cold smooth forms, the crevices, feeling the surprising power of the marble. I didn’t know the guards were in the corner, whispering to each other when I looked up. They had let me loose in there for many minutes, all in my own world. It changed my life, opened up a new world I have lived in ever since.

“Later, in other museums when I was older I tried to touch sculptures and learned that it was forbidden,” she continues. “I finally realized how the guards at the Borghese broke some rules letting me wander as I did. My foam sculptures in the 70s were all a tribute to that experience, making a place where people could touch the form, be inside of it.”

Painter Robert Natkin once confessed to me that in his desire to know Vermeer better—to somehow absorb him into his system—he crept close to one of the canvases in the Frick and managed to lick the surface while a guard was nowhere in sight. He wasn’t a kid at the time, and he certainly knew better (possibly saliva and varnish aren’t a good mix), but he was overcome by an irresistible impulse.

Many years ago, at a show of Mark Rothko’s paintings, I watched as a young woman, standing only a little more than a foot from the canvas, broke into a slow writhing solo dance, caressing her arms and flexing her legs. (Rothko would probably have loved it—he once said the best viewing distance for his works was about 18 inches from the surface.)

But most of us, especially as well-behaved adults, are content simply to contemplate, to ingest with our eyes and mind, powerful works of art. I recall sitting in the Courtauld Institute in London for fully an hour, admiring Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, trying to puzzle out its meaning and characters. But that’s nothing compared with critic Adam Gopnik, who told me a few years ago: “One of the things that’s really important to me and has been for 25 to 30 years is sitting with single pictures, with a notebook open for as long as I possibly can. I’m talking an hour, two hours, three hours.” The late Arden Reed argues in his last book, Slow Looking, that works of art unfold over time. He quotes impresario Peter Sellars: “The act [of painting] itself opens and refines consciousness by slowing down time as it focuses the eye.” And, after an eight-year infatuation with Manet’s Young Lady in 1866, he should know.

But his was an ongoing and protracted love affair, while my rediscovery of the Motherwell was more like that whiff of Ivory soap, a resuscitation and remembrance of an early passion.

In the last 30 years, in writing countless reviews and looking at innumerable shows, I’ve come to appreciate and admire many kinds of art—from the Minimalist sculptures of Donald Judd to the videos of Christian Marclay and Shirin Neshat to performances from Gilbert and George and Marina Abramoviƈ…and the list goes on and on.

But seldom does anything get the heart going thumpa thumpa like that Motherwell collage. Go figure.

A big p.s.: I still need addresses from most of you, so I can send out books after the new year to our “mishegoss” contest winners. I wasn’t kidding—really I have a ton of titles to give away because I have no more room in my house.

And Heather Bentz checked in a little late to the competition, but I include a collage from her series. “You Make Me Sick.” Because, Why not?

Thank you Ann for reminding me what a gift it is to have rich, emotional-filled memories of certain works of art. I was introduced in grad school in the late 80s to some incredible female artists who changed my view of the world and myself as an artist. Judy Pfaff, Susan Rothenburg, Mary Beth Edelson among many others, all sharing their unique passions, lighting the fire in the belly!

I too loved Frankenthaler and Motherwell while a student at Swarthmore, class of '66. My Welsh former coal miner professor thought Motherwell was a fraud but grudgingly gave me an A on a paper I wrote on him.