In the midst of all the harrowing hellacious news blasts from Washington and elsewhere, I was delighted to get an invitation to the inauguration of sculptor Ed Haddaway’s Early Morning Walk in Salida, CO, this past Friday. I opened his email and burst out laughing, as doesn’t happen often enough these days. Imagine the good folk of Salida encountering this larger-than-life sculpture on their own early-morning walks or evening strolls or maybe just cruising through town.

Though I could not attend the dedication, which would have meant about a six-hour drive round-trip in bad weather to and from Taos, Ed’s announcement set me to thinking about other funny art and artists of my acquaintance. When I was a wee lass studying art history at two esteemed institutions threatened with defunding by the Trump administration, I seldom encountered objects of amusement in survey courses of art down through the ages. With the possible exception of a few cut-ups like Giuseppe Arcimboldo, “fine” art wasn’t supposed to make you guffaw or smile or giggle.

Art was deadly serious. Art was the Parthenon sculptures and Leonardo and Michelangelo and Rembrandt and Vermeer and van Gogh and on and on right up till the early 20th century, when all hell started to bust loose. Particularly on the fringes of the School of Paris, where Matisse and Picasso reigned supreme. Duchamp and his fellow Dadaists began thumbing their noses at the whole notion of arty art, installing a urinal at the Armory Show of 1913 or painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa. Were people laughing? I’m not so sure. Gallic humor can be sly, insidious, and tough for Americans to read. Ditto jokesters like Paul Klee and Joan Miró, whose comedy tended toward the whimsical but who were rarely, I would maintain, laugh-out-loud amusing.

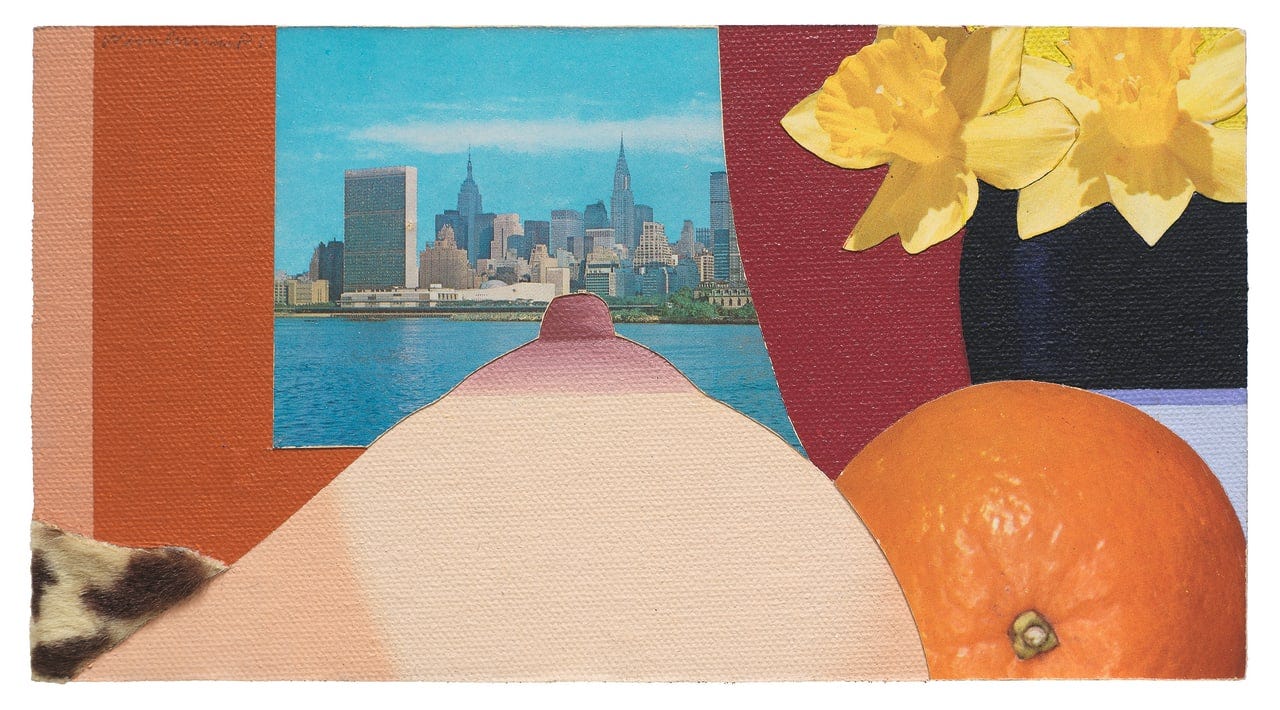

To my eyes, things don’t start to get truly funny until the Americans enter the fray in the latter half of the 20th century, when Robert Rauschenberg jams a stuffed angora goat into a rubber tire and Jasper Johns makes a pair of painted bronze ale cans in homage to Leo Castelli (Johns allegedly remarked about the famous dealer: “Somebody told me that Bill de Kooning said that you could give that son of a bitch two beer cans and he could sell them. I thought, what a wonderful idea for a sculpture.”) Here at last was good old American smartass humor—robust, prankish, and as in-your-face as a lemon meringue pie in the kisser. Was Pop Art funny? Roy Lichtenstein’s comics, Warhol in his fright wigs, Tom Wesselmann’s fruits and nipples. Yes, much of it. Ceramists Viola Frey and Robert Arneson kept things waggish on the West Coast. Even the young Bruce Nauman posing as a fountain in Self-Portrait as a Fountain. Eurotrash like Maurizio Cattelan may be laughing all the way to the bank with their duct-taped bananas, but the Americans just wanna have fun!

And so do many of the original members of the Vasari21 site, as Ed Haddaway made me realize when he extended his invitation to Salida. So I present them here, not in any particular order, and I realized when I was halfway through writing this that I had many candidates and much to say, and so I will be bringing you more next week. You need this. You really do.

Ed Haddaway

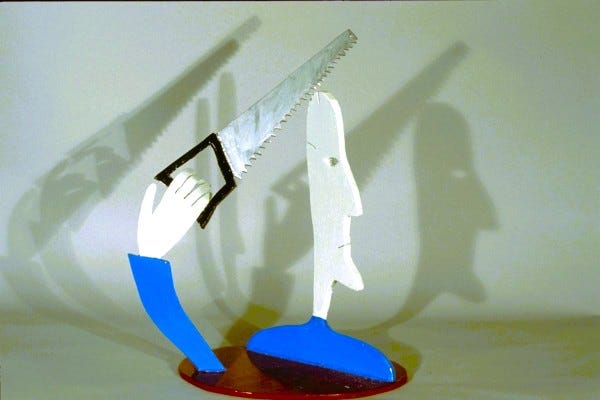

Haddaway grew up in Fort Worth, TX, but really came of age as an artist when he moved to Albuquerque, NM, in his mid-twenties. Though his work contains nods to Calder and, less obviously, to David Smith, there’s a jaunty buoyant cartoony aspect that is all his own—along with elements of the Southwest, like cactuses and hints of other spiky plant life. He’s also attracted to old patinas and rusty surfaces and “things being built up and falling apart at the same time,” as he explained in a PBS documentary about his work.

“I’ve always paid a lot of attention to dreams,” he says. “I wrote them down. But then they scared the hell out of me. So I quit doing that.” Making art, he claims, allows him a pipeline to the unconscious. “Carl Jung’s ideas gave me a rationale for what I did. Not that I am a big follower of Jung, but it seemed we were on the same wavelength.”

Hoping to attract more visitors to the Wright Contemporary, I asked him to install one of his tall and welcoming assemblages, Dreams 3, near the sidewalk outside the gallery. I don’t know that it spoke to the masses, but it made me happy every time I admired it from my office window.

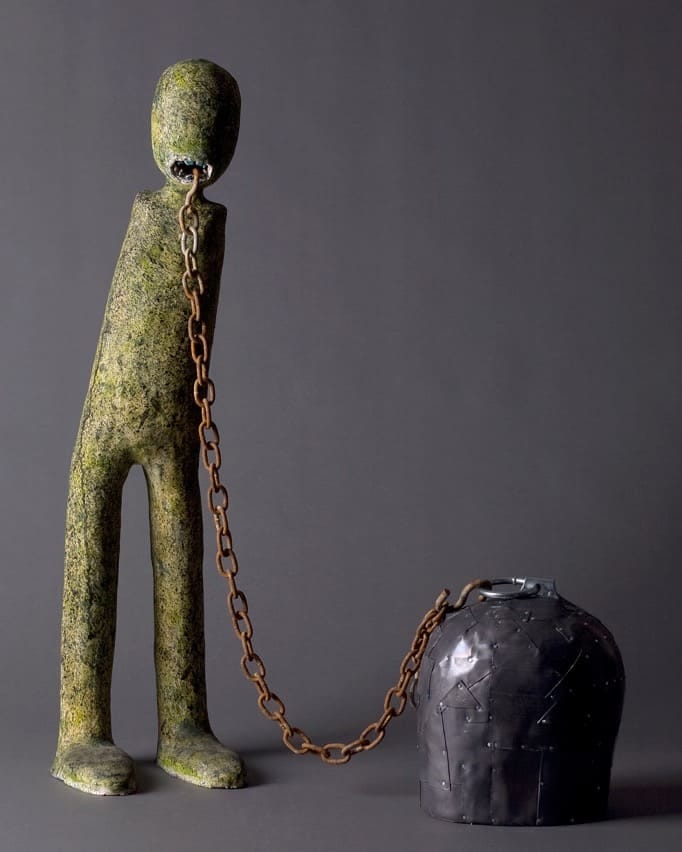

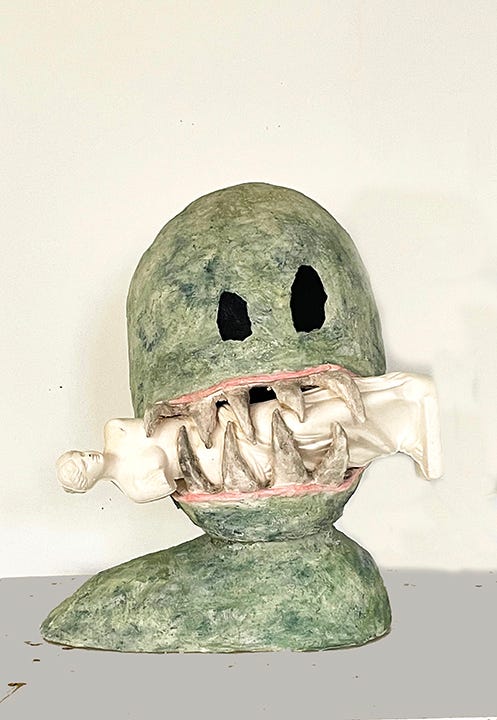

Melissa Stern

Stern was one of the earliest to sign on to Vasari21 way back in 2016, when she sent a couple of jpgs of her work that had me grinning from ear to ear. At the time I profiled her, she had a traveling show called “The Talking Cure,” which I described as a collection of sculptures that are only too eager to tell you about the complicated workings of their inner lives. Stern asked a group of twelve writers to come up with scripts for her quirky characters and found a dozen actors to read them. You could summon these up on your smartphone and hear their stories. This went way beyond Pygmalion chiseling Galatea into life; now she couldn’t stop yakking about it.

Stern grew up in Philadelphia, where her mother was a designer for department store windows, and has lived in New York, San Francisco, and Belgium. She admits to a “good ten years of wandering” before she began to put herself together professionally. “I always made things, I had galleries,” she says, but she and her husband didn’t have the feeling that they would stay in one place for long until returning to New York from Brussels.

In the nearly ten years that we’ve been friends, she has exploded artistically and professionally, with series whose names give the game away—“Family Values,” “Strange Girls,” and “Housebroken.” (Her drawings crack me up as much as the sculptures.) She’s had numerous shows in venues from Brooklyn to Shanghai and has been featured in Sculpture magazine. And though she elicits bemusement, there is often a sweetly therapeutic subtext. Of “The Talking Cure,” she noted, “I inadvertently stumbled on a theme people respond to. I never imagined I would make something that would resonate so deeply and touch so many in different ways.”

Leslie Fry

Though I’ve never met her, and we’ve never talked at length, I’m convinced Leslie Fry communes with magical woodland spirits. I think of her primarily as a sculptor, but her prints are also pure enchantment. And funny.

As she writes on her website: “Over 33 years I’ve nurtured the semi-public sculpture garden adjacent to my studio in Winooski, Vermont. Sculpture provides full-sensory experiences, especially when accessible in outdoor spaces rather than inside museums or galleries. Visible from the street, the garden has become well known, and I give personal tours to those who are interested. Winooski is Vermont’s most diverse and densely populated community, with more than 36 languages spoken in this one-square-mile city. I continue to integrate sculpture and landscape toward my ideal sculpture environment – one that is accessible to people from all walks of life and sensitively scaled for human interaction.”

In the immediate wake of the pandemic, Fry lost both an adjunct teaching post at Dartmouth College as well as a lucrative sculpture commission for a New York City hotel. During a summer residency in Maine she created images unlike any work she had made before. “It was July, but it was really cold,” she recalls. “So cold in the mornings that I would walk for three hours all around the island just to keep warm while photographing the amazing, dramatic landscape. I had brought with me leftover bits and pieces from years of collage projects. After a while I thought, Why don’t I place some of these ‘characters’ from my collage leftovers into the landscape?” The upshot is a magical series called “Norton Island Visions” that imagines, say, a medieval city with ramparts and towers tucked among the rocks at the water’s edge, or a Flemish maid, deep in the woods, reading her prayer book at the base of a moss-covered tree. During her last days on this uninhabited island, she sculpted two “bird people” from twigs, moss, seaweed, pinecones, and old pages from the “Sirens” section of The Odyssey. She then photographed these figures in the landscape for a series called “Wanderers.”

“It’s been a constant learning process,” Fry says. “I spent a couple of thousand dollars having these beautiful prints made, in editions of ten. I did make sales. But I started to realize that nobody cared if it was a limited edition. They simply chose images that they liked.”

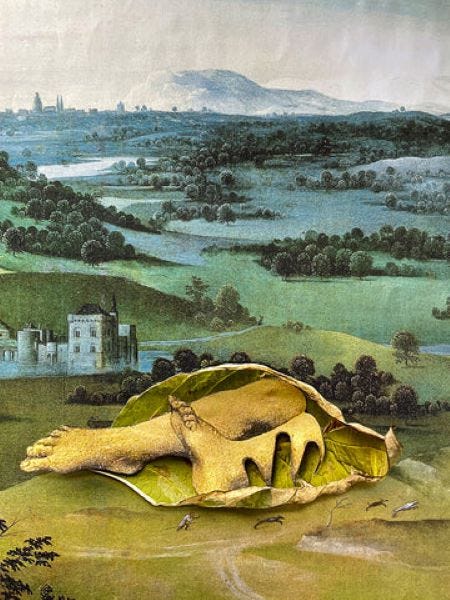

Then she hit on the idea of printing on aluminum (super durable and no need for framing). She started photographing another series called “Vermont Life,” again using bits and pieces (a disembodied leg, a headless torso, an early Medieval townscape) embedded among trees or set against a lakeside. Others, like “The Lives of Dahlias” and “The Dark Leaves,” continue in the same vein. Her prints, in many sizes and printed on archival paper or aluminum, are both amusing and affordable. You can’t beat that.

Please stay tuned for more drollery next Sunday.

,

A nice piece about humor in art! Thank you! Generally speaking, I find humor mostly lies n comics strips rather than fine art, and my own fave is Ernie Bushmiller's Nancy (from the past, of course). It interests me that abstract art is mostly tragic, or at least "not funny"--certainly never LOL funny the way figurative art can be.

Only a few abstract artists stray over into the humorous. My aesthetic hero, Miró, is one who comes to mind immediately, and he's influenced me in my own art to push toward that which makes me and the (small) audience I have for it smile.

You are correct. I needed this. Great article. Thank you, Ann!