To take my mind off the madness of bad King Donald and his clueless minions, I have been giving more and more thought to funny art. “Funny” is a catch-all term, like “beautiful,” encompassing many subsets: comic, wry, humorous, satirical, witty, whimsical, and hilarious, among others. And one art lover’s response may be entirely different from another’s. I still recall encountering Robert Mapplethorpe’s Man in Polyester Suit (1980), a portrait of a black guy in three-piece business attire with his uncircumcised penis hanging out of his open fly, in one of the first galleries of a show devoted to the artist at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1988. I thought it was laugh-out-loud funny, unexpected and even rather tender (its subject was Mapplethorpe’s lover, Milton Moore). Others, of course, were not so amused; both the far right led by Jesse Helms and the gay Black community of critics and artists were appalled. Why was I, a straight white chick in her 30s, so amused. I don’t know!

Was this a joke, and if so, did it follow the rules of many jokes: If you have to explain how it works, it’s not really funny, at least not to the uninitiated.

Visual art has its genres, but when it comes to humor, they are not as easy to pinpoint as in literature. Consider the way comic literary works can be neatly parsed, at least in the past, into distinct categories: satire (Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal), the comic novel (Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones), humorous verse (Lewis Carroll’s The Walrus and the Carpenter), comedy for the stage (Shakespeare, Pinter, Albee), farce and slapstick (Charlie Chaplin and Georges Feydeau). In these, the author expects to elicit laughter and smiles, or the work is a failure.

Assessing and understanding humor in art history is not as easy. Rummaging around through the past, one finds a few obvious examples of forthright satire, like William Hogarth’s series “Marriage a la Mode” or Daumier’s lawyers and court-room dramas. A few contemporary cartoonists, like Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman, lift the comics into the realm of fine art and even show up in museum surveys. But what of artists who were never really considered jokesters, like Hans Holbein and his Ambassadors, incorporating an anamorphic skill at the bottom, or Parmigianino in his Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror? Were these supposed to be funny, or were they simply demonstrations of the artist’s virtuosity? I’m convinced there are lots of sly japes in older art that we’re simply not picking up on (in-jokes in Dutch still life, for example) because contemporary viewers can’t spot the witticisms through a 21st-century lens. One reader of these bulletins suggested that cave art tens of thousands of years old may have been amusing for its makers and viewers, the equivalent of “The Flintstones” after a hard day of hunting the woolly mammoth. But in the end we just don’t know….

To segue quicky to the present, and since I’ve been promoting the artists who were part of the original Vasari21 website, here are the ones who tickle my funny bone, even if they didn’t mean to.

Eleni Mylonas: Born and raised in Greece, Mylonas emigrated to the U.S. in the late 1960s to study comparative journalism at Columbia University. She landed prestigious internships with both Look magazine and WGBH-TV in Boston, and from editorial assignments she branched out to develop her own projects. Her first big breakout was a show of photographic works about Ellis Island at PS 1 in 1986, and since then she has pursued a varied career that encompasses performance, video, installation, sculpture, and painting.

“I strive to create bridges between different realities,” she says in her artist’s statement, and because she has divided her time between Greece and America, she’s managed to establish a stronger presence in Europe than in New York, which has nonetheless been her home for nearly 50 years. Often her work is motivated by politics or by random encounters with the detritus that swamps our world, such as the debris that washes up on the beaches of Greece.

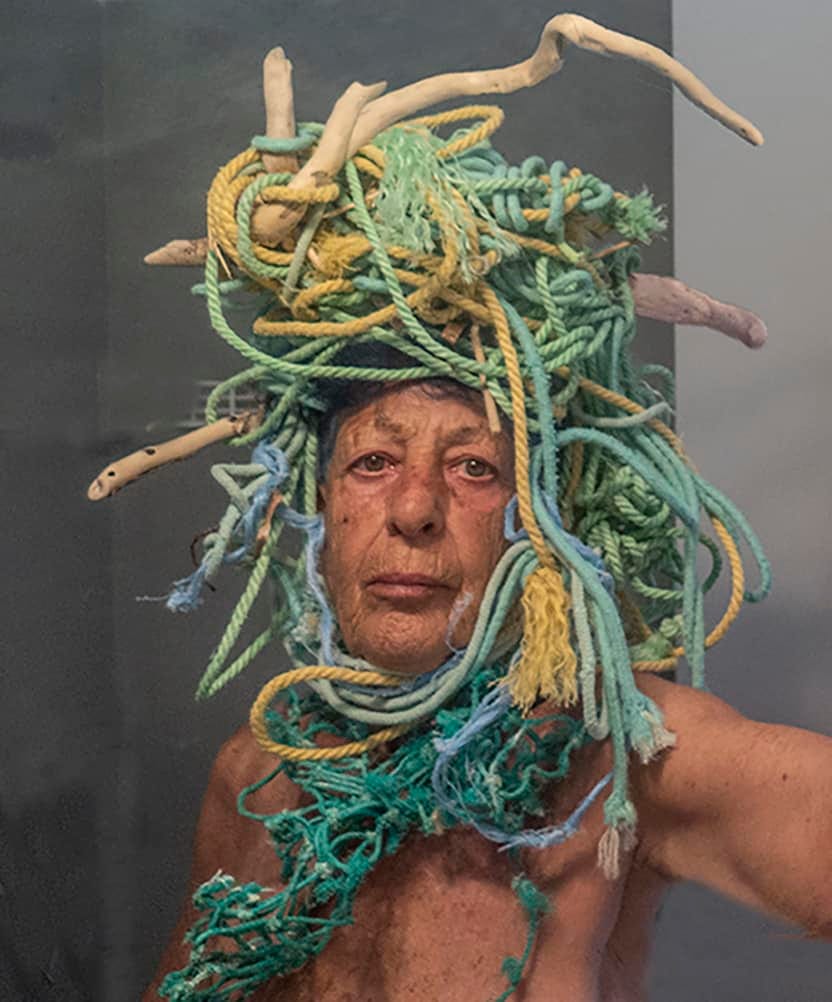

The “Alternative Portraits” series, shown here, was first inspired by the Arab Spring, the anti-government protests that erupted across much of the Arab world, beginning in 2010. “At the start, there was no gunfire,” Mylonas explains. “People would go out from their houses with household items on their heads to protect themselves. I saw the pictures, and they impressed me because the objects were funny but necessary at the same time. I started making drawings and paintings of them and eventually I put items on my own head. Inspiration came from the protestors who were protecting their heads with bread, with plastic bottles, with foam—anything they could get their hands on.”

In time, the series found its inspiration in diverse other sources, as explained in the captions, and resulted in a show called “The Cursed Serpent” at the Benaki Museum in Athens. “Stereotypical imagery is manipulated with remarkable skill to suggest new identities and roles,” wrote curator Christina Petrinou. “Mylonas assumes those roles with a stately deadpan expression that bears no trace of narcissism, investing each form with a ritual-like quality reminiscent of an Old Master portrait.” All are archival pigment prints, 42 by 60 inches.

Linda Vallejo: In her five decades as a working artist, Vallejo has tackled issues of race and culture in a range of mediums, including painting, prints, drawings, sculpture, and installation. Art lovers in Los Angeles and elsewhere caught up with her provocative narratives in a recent show at parrasch heijnen (she has an impressive roster of exhibitions nationwide, along with works in the permanent collections of the Hammer Museum, the Broad Foundation, and El Museo del Barrio).

In her cheekiest project, still ongoing, the artist has pointed to the lack of representation of her Mexican-American heritage by turning everyone brown. “Make ’Em All Mexican” takes works from high art to kitsch, from the Winged Victory of Samothrace to garden gnomes, and confers Latino status on all. “When you begin looking at it, you begin to see that we are missing from this conversation,” Vallejo told the Los Angeles Times. “I’ve basically reappropriated culture, taken it back and I’ve made it brown, so everybody gets to be brown.”

Born in Boyle Heights, one of the oldest Chicano/Mexican neighborhoods of Los Angeles, in 1951, Vallejo spent her first few years in East L.A. before living in Germany, Spain and Alabama — moves driven by a father who was a colonel in the Air Force. It wasn’t until she relocated back to Southern California in the late ’60s that she connected with her Mexican American heritage.

“I grew up Middle-American,” she told the L.A. Times, “My parents were punished in grade school for speaking Spanish, so they were doing everything they knew how to do to assimilate, to become American.”

One of Vallejo’s first pieces in “Make ’Em All Mexican” was based on the classic series of children’s books “Dick and Jane,” in which she darkened the characters’ skin — not enough to be jarring but just enough to widen the scope of representation. The book was a staple of elementary school education in the 1950s. And all the characters were “white, blue eyes, very fair, this happy family with the dog. So there’s a sense of exclusion even to a child, and children are very sensitive to these kinds of things.”

Now all grown up, Vallejo is changing the canon, firmly tongue in cheek.

Ira Wright (aka Stephen Monroe): The benefactor of the short-lived Wright Contemporary in Taos, NM (of which I was the major domo for about three years), Wright came of age in Kalamazoo, MI, and studied industrial design at the storied Cranbrook Academy. Because his father had a connection with Litton Industries, which was still in its infancy but would later become one of the largest conglomerates in the world, Wright moved to Orange, NJ, after graduation. He designed the cases for early computers, which were then about the size of a desk, and had the distinction of naming a custom color “Tahitian Sunrise.” After a few years, he returned to Kalamazoo and worked at a succession of jobs—including gigs as an art director and graphic designer at an ad agency, a foundry worker, and a teacher of studio art and art history at local colleges.

As a single father, the artist often took trips with his kids when they were teenagers. One summer the family wanted to go somewhere out west and ended up in Santa Fe, NM. “And I said, that’s where I’m going to move,” he recalls. “The light, the landscape, the tranquility. There was a peacefulness that didn’t exist in places where I’d lived before.”

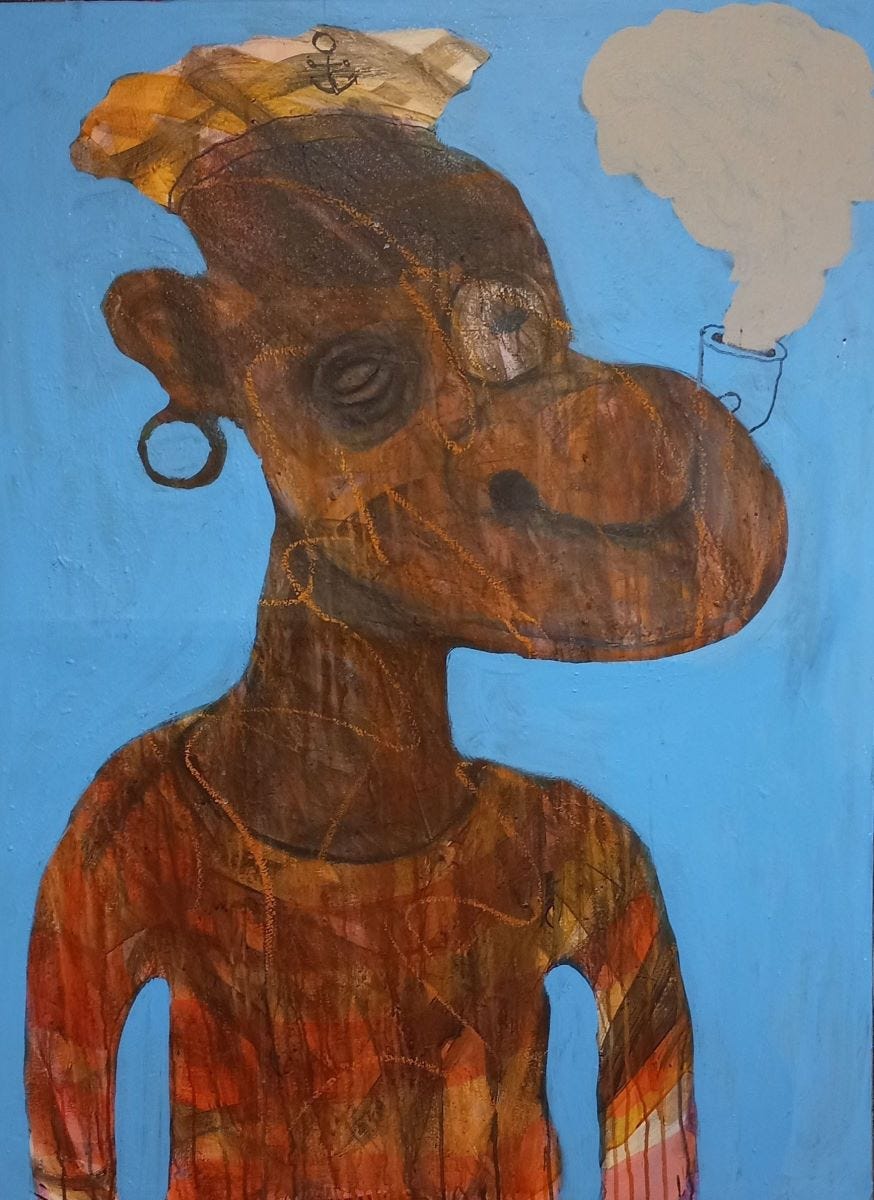

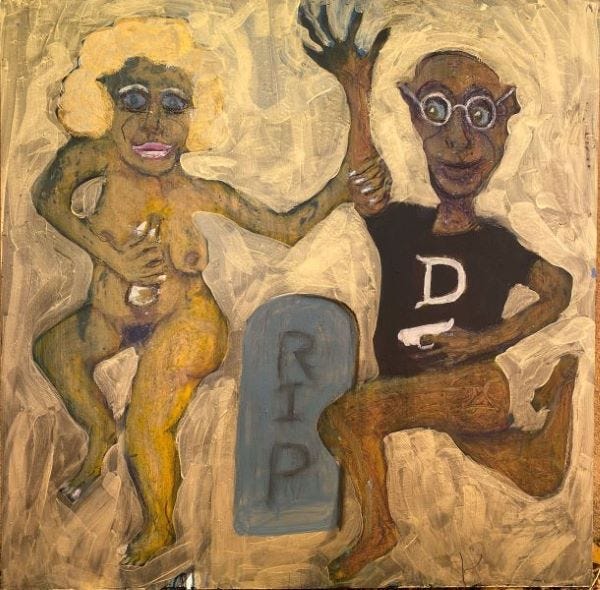

In the Southwest, Wright devoted more time to painting and drawing and developed a vision that was at once harrowing, comic, and sometimes deeply disturbing. He made large satiric paintings taking potshots at religion and the battle between the sexes, acerbic self-portraits, and a series of delightfully loony cars made from found materials. It was a rich and strong career (though without many shows or collectors), and we were glad we could put together a mini-retrospective of works before his death in 2024.

Isabelle Plat Though not technically a member of the original Vasari21 gang—because I didn’t make her acquaintance till a couple of years ago—Plat brings to her drawings and installations a kind of wit that seems ineffably gallic, reminiscent of foremothers like Niki de Sainte Phalle and Louise Bourgeois (she was born in France and divides her time between New York and Paris).

The title of one of her shows in Paris was “Putting Oneself in the Skin of the Other,” and it is an apt summation of what the artist is all about. Plat, who has been reaping acclaim for exhibitions in Europe since the 1980s, uses clothing donated by friends, human hair from styling salons, and accessories such as boots and socks to create in-your-face large-scale assemblages that she calls “portraits d’usage” (“usable portraits”). A highly articulate woman who is affiliated with Galerie Eric Mouchet, Plat has written about the tradition of “useful” or “usable” sculpture, which includes artists like Donald Judd, Scott Burton, and Andrea Zittel. In its simplest form, a useful item becomes a sculpture, as in Burton’s benches for a plaza in midtown Manhattan. In previous exhibitions of Plat’s works, viewers could slip inside the different elements—a “coat,” for example, or actually sit on her “Pants Seats.”

In the show we installed at the Wright in the summer of 2023, Plat was more concerned with reconfiguring some of her signature works to create a new kind of portraiture. “I associate the human body with the bubble that everyone creates for themselves in the real world,” the artist has written. “If Cubist painting subjectively deconstructed people and objects and showed us their hidden sides, my installations conjure with the internal life—materials that bear the traces of life: already-worn clothing, agglomerations of human hair, and other traces of the living subject.”

A p.s. for this post: This photo was part of the Key West 2025 Mango Festival, in which entrants were invited to riff on works of art. The author is Mark Hedden, a local photographer, writer and birder. Fiendishly clever, and I’m sure you can guess the inspiration.

Yes--I often find myself laughing at art --sometimes it's from the simple pleasure of seeing something new.

Very provocative and rich material for further thought. Something like unleashing a Pandora's box of humor and satire. So necessary for the human mind. Brava!