I am not sure what led me to start thinking about Édouard Manet’s great series of paintings and lithographs about the execution of the Emperor Maximilian in 1867, but I know that I have been wondering what kind of art will come out of these tumultuous times. I wondered the same thing at the start of the last Trump administration, and am republishing much of that essay here, because I still agree with my conclusions nearly eight years ago.

But first a word about Manet. In 1864 Napoleon III of France, whose regime Manet and several of his Republican colleagues strongly opposed, sent the second son of Archduke Franz Karl of Austria to become emperor of Mexico in pursuit of the French ruler’s imperialist ambitions. (This might be roughly akin to Trump sending J.D. Vance to Greenland to become prime minister, if such a thing were possible, and Trump probably thinks it is.)

The Mexicans were having no part of this. Maximilian faced significant opposition from forces loyal to the deposed president Benito Juarez, and his puppet empire collapsed after Napoleon withdrew French troops in 1866. Maximilian was captured outside Queretaro in May 1867, sentenced to death at a court martial, and executed, together with two of his generals, a month later.

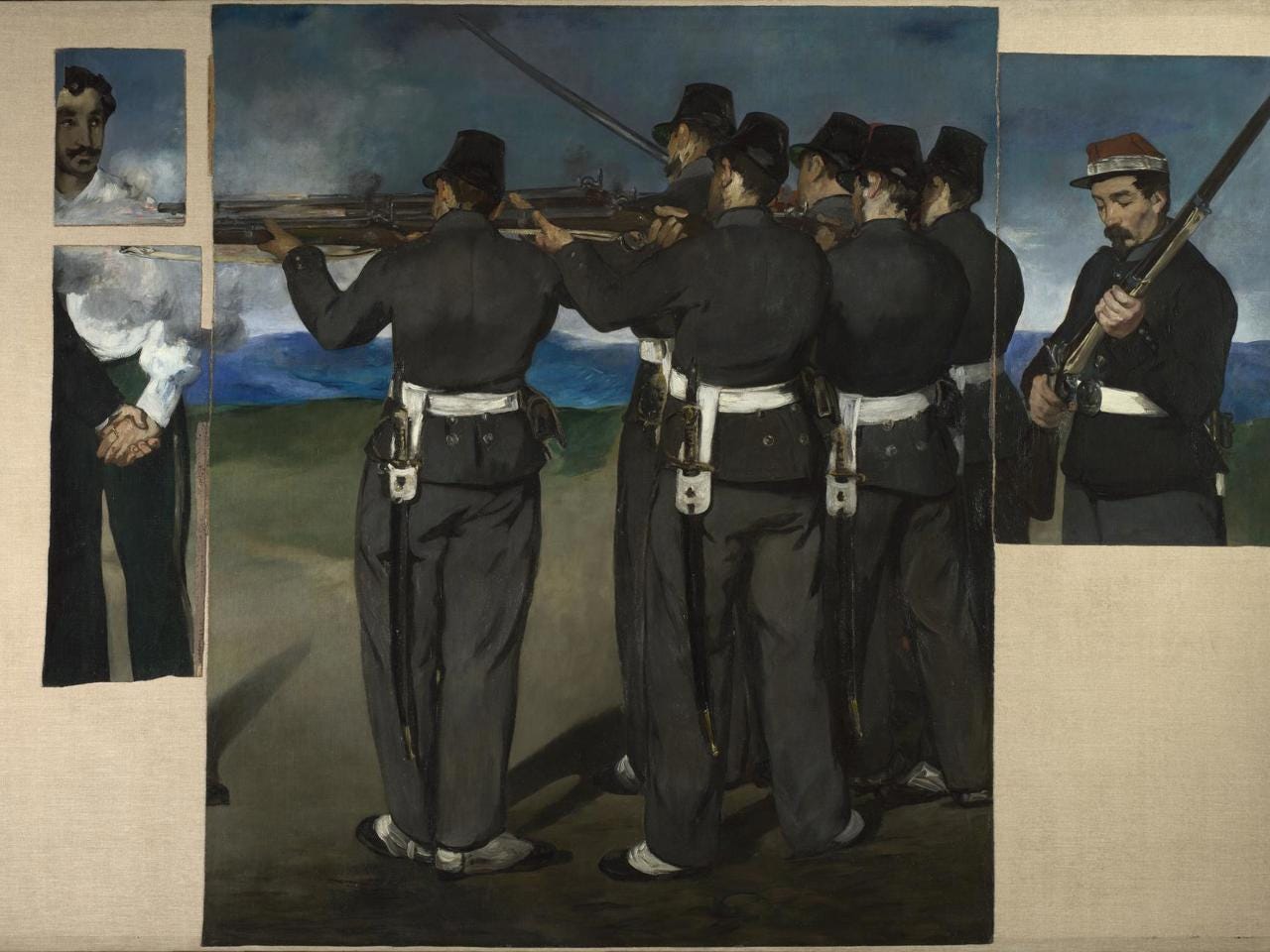

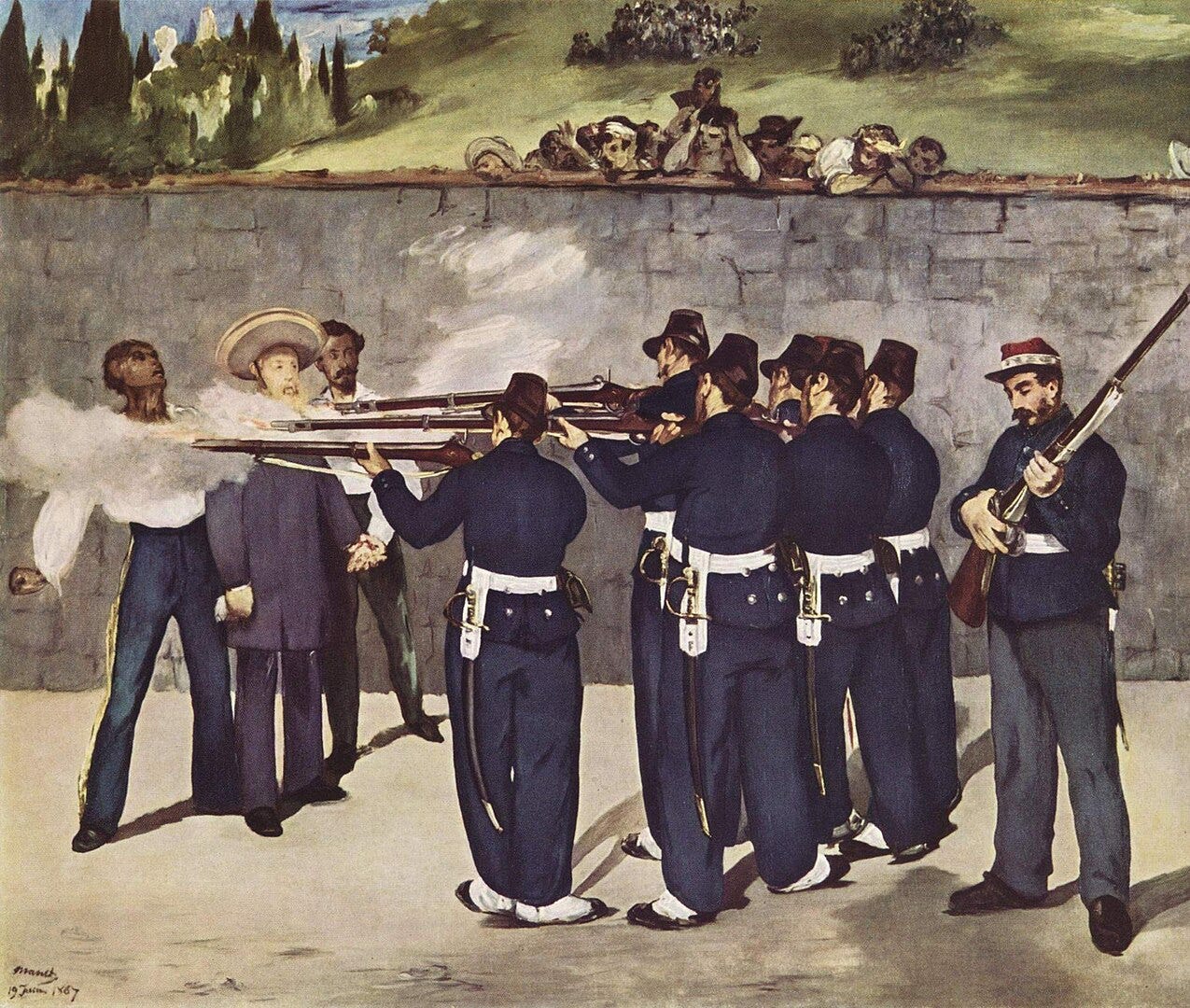

Many in France were outraged, including Manet, who set to work on paintings (there would be three in all) commemorating the event and influenced by Francisco de Goya’s masterpiece The Third of May which immortalized Spanish resistance to the armies of the original Napoleon in 1808 (Manet had seen and greatly admired the painting in 1865). The works, and the lithographs he made from the original compositions, were never shown in his lifetime, because in the words one curator (who has a marvelous talk on the subject here) “the event had the potential to shatter the prestige of France internationally.”

Manet was doing something new in the history of art, a kind of mash-up of contemporary reportage and grand history painting that offers an immediacy hitherto unknown in painting (check out that smoke, the small crowd gathered to gape on a balustrade, and the soldier at the far right calmly loading his rifle to deliver the coup de grace).

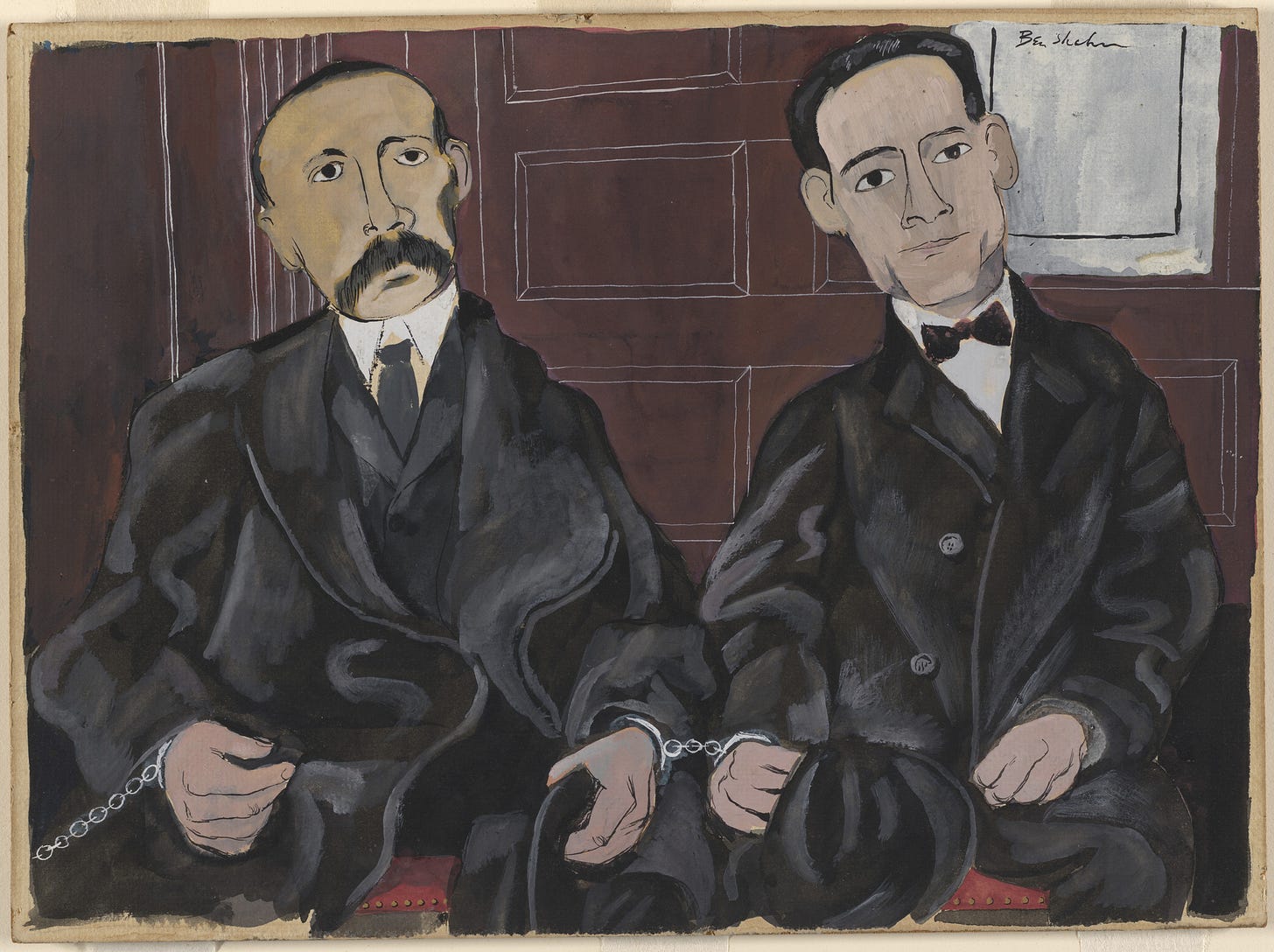

As far as I know, his innovations were never repeated in European painting, and it’s not till Picasso’s Guernica that we find a similarly powerful kind of protest art in a whole different language. (Some might argue that Ben Shahn, who is having a moment at the Jewish Museum through October 12, offered up moving social realist remonstrations during the Depression, but I don’t find these anywhere close to the powerful statements of Picasso or Manet.)

Every era has its painters, photographers, visual satirists, and even video and performance artists who take as their subjects the appalling inequities around the globe. To cite just a small handful of recent examples, Kara Walker and Kerry James Marshall focus on the ongoing problem of racism; Banksy takes to the streets with subversive epigrams and graffiti; and Ai Weiwei has made Chinese government corruption and cover-ups the focus of all his recent endeavors.

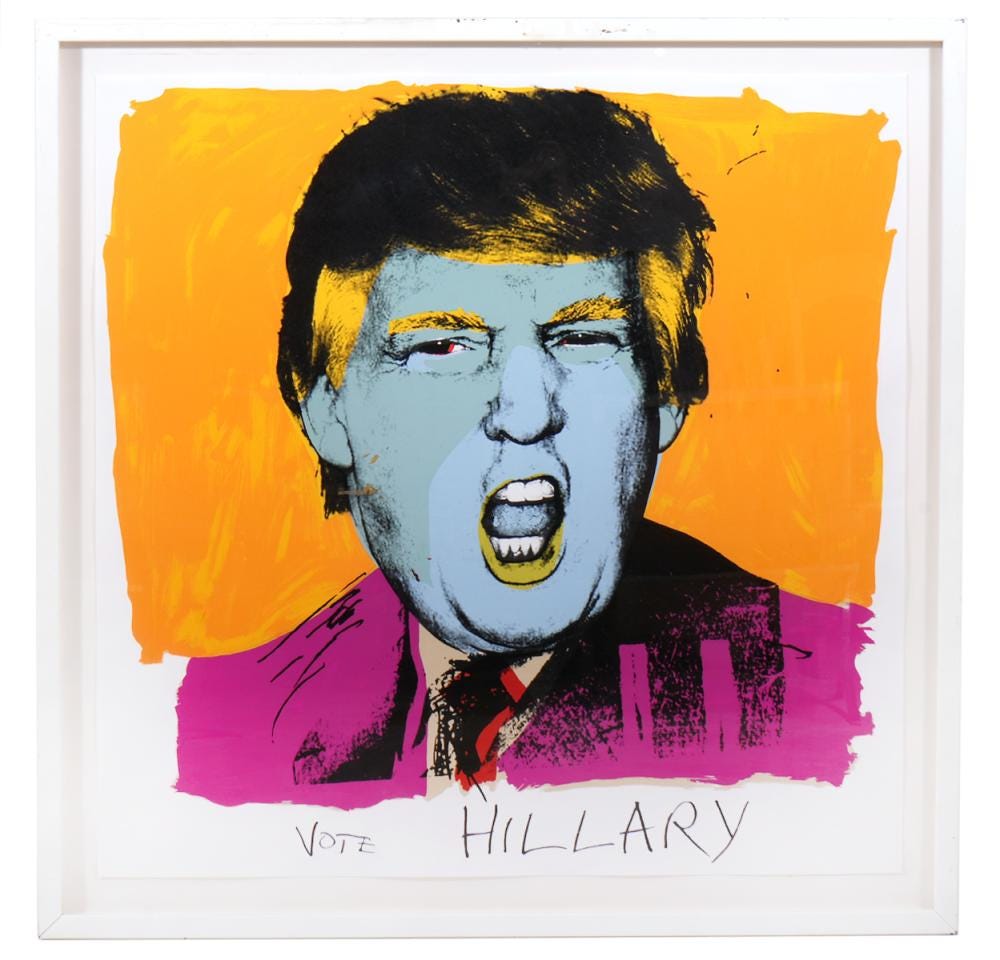

In its first incarnation, the Trump administration inspired its own brand of protests among artists, perhaps beginning with Deborah Kass’s indelible portrait of the snarling president-to-be during the election season. Shepherd Fairey offered a new line of posters featuring portraits of marginalized people, like a Muslim woman wearing an American flag as a head scarf. Richard Prince returned the $36,000 fee for a portrait of Ivanka Trump (why was he painting her in the first place?). And Christo announced that he would not build “Over the River,” a vast public artwork consisting of a silvery canopy above 42 miles of the Arkansas River “because the terrain, federally owned, has a landlord he refuses to have anything to do with: President Trump,” according to the New York Times.

These are all noble and stirring gestures, generally so visually appealing that they rouse the senses on some level. But how often do they have any real effect on our sentiments or our inclination to take action—to hit the streets, stage a sit-in, call our representatives, write letters, or perhaps quit our jobs and leave the country? If you’re not already converted, you probably will not change your mind because of an artist’s agenda, no matter how powerfully presented. (This may not have been the case in Manet’s time, when he could not show his paintings of Maximilian or publish the lithographs because the government seemed to fear retribution.)

I would maintain that political or protest art is wonderful to behold but does very little to nudge public opinion, and often results only in the persecution of the artist. (Of all those cited, Ai’s art, which includes blogging and other internet activism, has probably had the most impact, and for his attempts to expose the rot at the core of Chinese politics, he has been imprisoned, forbidden to leave the country, and seen his studio demolished overnight.)

The late Robert Hughes argued that so-called “fine art” does not really have the power to sway beliefs and attitudes. “What really changes political opinion is events, argument, press photographs, and TV,” he observed in one of his characteristically tart essays. And when I think back to documentary photography in particular—Nick Ut’s shot of a screaming napalmed Vietnamese girl, the images that emerged from the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib—I’m inclined to agree. If those, and the dogged reporting that accompanied them, didn’t affect your opinion of two very lunatic wars, then you are made of stone.

Already I think we are seeing that documentary photography and video, not painting or sculpture, are the most powerful means to sway public opinion. The images of millions turning out to march peacefully, of immigrants in Venezuelan jails, of a United States Senator wrestled to the ground and handcuffed—even of Trump dozing at his own lackluster military parade—will always speak louder than any art in a museum or gallery. And who knows what kind of documentary evidence will surface after last night’s bombing of Iran.

Which is not to say artists shouldn’t try. The world would be a poorer place without their outrage.

Ann, Adding to the discussion :--)

I would argue that culture is not a quid pro quo situation in that a political work doesn't cause an immediate return or response. BUT (and this is a big but) art matters.

If it didn't, the USSR and Hitler wouldn't have spent so much energy trying to suppress abstraction. Similarly, post WWII USA wouldn't have invested so much money and effort in promoting the "American" arts in Europe alongside their Marshall Plan. And Trump -who I am guessing has cultural taste akin to his culinary love of fast food-- saw it as important to take over the Kennedy Center, the Smithsonian, etc.

Art matters not because of its specificity but because it sets up a tone, an ethos. And even more importantly, it effectively records the history of the time. "Raft of Medusa" by Gericault was painted in response to the greed of slave ship owners heading to what we call Senegal. It exists now mostly as a compelling (non political) image of tragedy, but it also records a piece facts that were of concern in France at that time--just as Martha Rosler's photographic collages recorded the horrors of the Vietnam War 150 years later.

Good piece, and we need more attention drawn to this issue. I have drawn much the same conclusion about political art. The artists and the art world get a lot out of it, but the idea that it has any real impact on politics is at best a delusion, at worst a kind of ego-trip on the part of artists. Here's a piece I wrote on the exhibition "Modern Art and Politics in German 1910-1945," which closed today (at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth). All that German protest art during those war years, and not a shred of evidence that any of it affected the politics.

https://twocoatsofpaint.com/2025/06/art-versus-politics.html?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=art-versus-politics