The Strangest Story I Ever Told

Dueling scholars, a Renaissance genius, and one slender marble boy hidden in plain sight for decades

Continuing our discussion last week about reporting, I offer an example of the work that happens before a “hot” news story reaches print. Now that the art magazines have drifted to mere online ghosts of their former selves, we don’t see much of this type of investigation. Ah, the good old days!

In late January of 1996, the New York Times ran a front-page article that knocked the socks off art lovers and art historians worldwide. The Times leading critic, John Russell, announced that a scholar of Renaissance sculpture from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts had carefully examined a “three-foot-tall marble statue of a naked, curly-haired youth, set on an ancient Roman altar” inside the lobby of the French cultural attaché on Fifth Avenue and pronounced its maker be none other than Michelangelo Buonarroti.

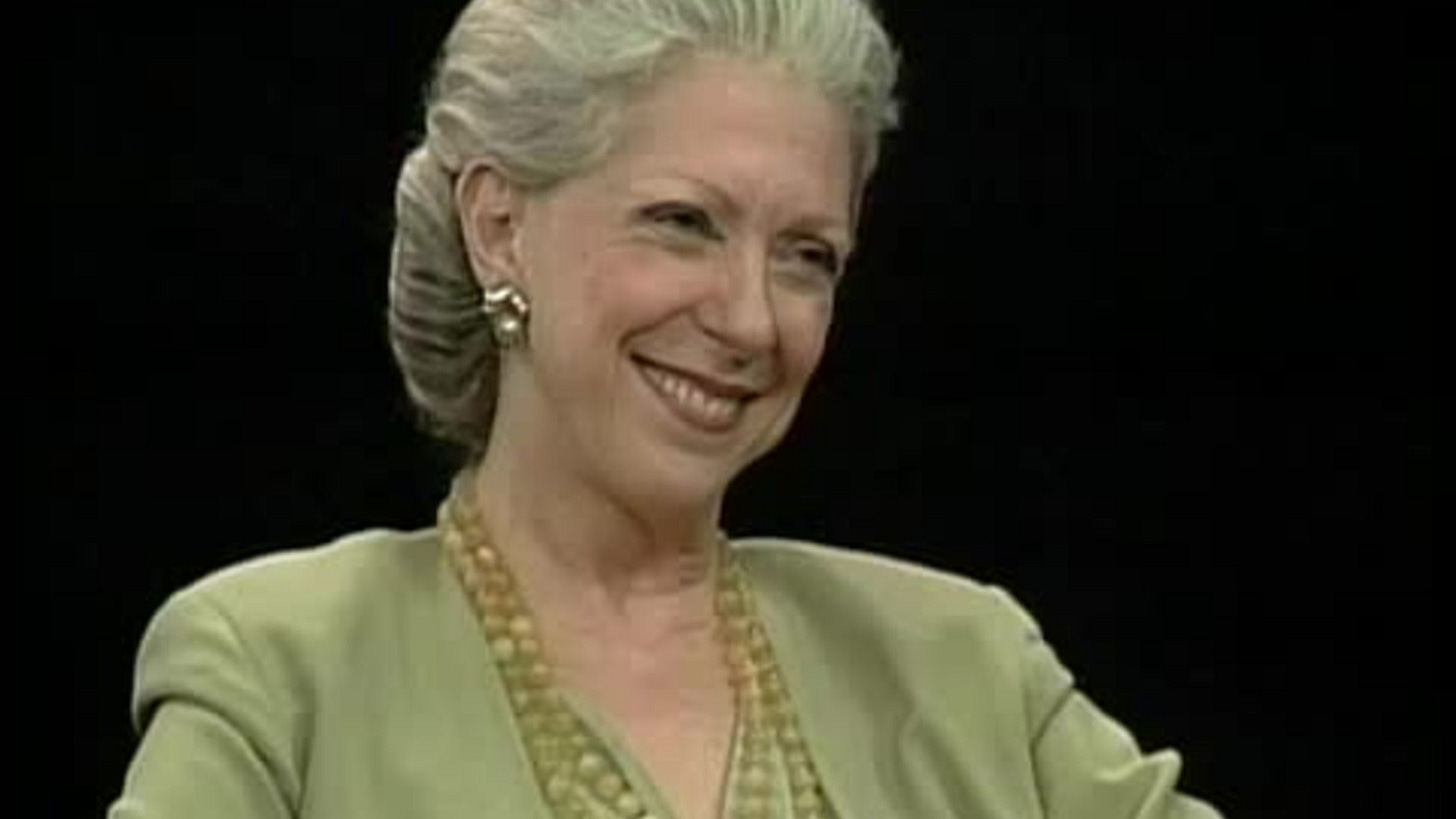

Kathleen Weil-Garris Brandt, the scholar in question, an attractive blonde in her early 60s, claimed the statue was probably a depiction of Cupid, made when the genius was only about 20 and still in the workshop of his teacher, Bertoldo di Giovanni. Almost immediately she was on the Charlie Rose show on PBS, repeating the story she told the Times. One rainy night the previous October, walking past the building that housed the cultural services for the French embassy, she noticed the lobby brightly lighted for the opening of an exhibition.

“I literally pressed my nose against the glass,” she recalled, “and I recognized the sculpture as a piece that’s been missing since 1902.”

In tracing its history, Brandt revealed that the statue went to a dealer in Rome after it failed to sell at Christie’s in London. Claiming the work was a newly excavated antique—even though the catalogue attributed it to Michelangelo—the dealer sold it to architect Stanford White, who “bought such things by the truckload,” according to one historian. White procured it for the house he was designing for the Payne Whitney family (Harry Whitney was a wildly successful turn-of-the-century businessman who married Gertrude Vanderbilt and died in 1930, leaving a $62 million dollar fortune, a vast sum then and now). When the statue arrived in New York, White placed it on a stone basin in the rotunda of the entryway. And there it remained even after the French government bought the building.

The little Cupid had not been entirely ignored prior to Brandt’s “discovery.” On the basis of the 1902 photograph in the auction catalogue, Alessandro Parronchi, a Florentine art historian, claimed the sculpture as Michelangelo’s in 1968. Robert Schoen, a New Orleans-based sculptor, saw the statue in 1984 and tried to bring it to the attention of Philippe de Montebello, then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His dealer, Timothy Foley, hoped to pry the work loose from the French and sell it to the Getty. And in 1986 journalist Jesse Kornbluth also sought the Met’s endorsement for a feature story he wanted to publish in New York magazine (the museum declined to look at the work). James Draper, curator of European sculpture at the museum, said he had a vague memory of glimpsing the work from a Fifth Avenue bus and dismissing the Michelangelo attribution.

Next thing you know, the Village Voice was publishing a satirical story about lost Michelangelos cropping up everywhere: at a graveyard in Queens, an Italian restaurant on Staten Island, an overgrown back yard in Brooklyn.

The challenge for ARTnews, at that time a monthly magazine for which I worked as a senior editor, was to find a way to present Brandt’s claims along with the controversy that was bound to ensue when the daily press would already have covered many of the finer points. How could we come up with a new angle?

I went to look at the sculpture and immediately had doubts of my own. First it was damn near impossible to see anything through the double set of doors, each protected by elaborate wrought-iron grillwork, in broad daylight, let alone on a rainy fall evening. There was no way Brandt could “literally press her nose to the glass,” as she claimed when she first spied the sculpture and decided that it might be a work of the young genius. Because the grill work would have prohibited her pretty face from getting any kind of look at all.

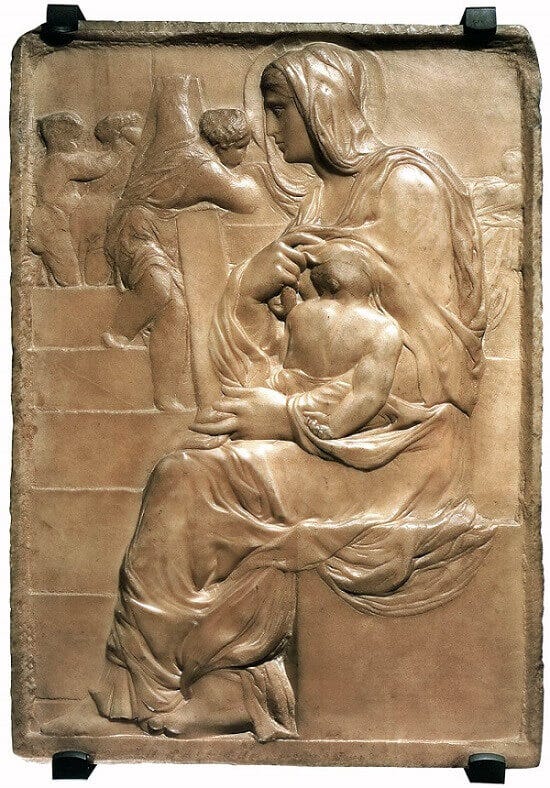

And then I went inside to study the work firsthand. Now I am no scholar of Renaissance sculpture, but this thing looked pretty lame to me. The butt and back are not well articulated, the neck skews at an awkward angle, and the pose is lacking in any of the dynamism we associate with Michelangelo. The contemporaneous, firmly attributed Madonna of the Stairs (or Steps) from the same year, by contrast, shows an incredible sophistication from the young sculptor. “The composition of the sacred group is very original, at the same time blocked and dynamic, with the Virgin in a prophetic attitude, as she lifts her dress to feed or protect the child asleep, and generates a movement spiral thanks to the arrangement of opposite limbs,” notes Wikipedia. (I especially love the hands, even the baby’s, in this one.)

But, hey, as said, I’m no scholar and my job was to report.

I talked with Brandt before the magazine decided on any way to present her findings, and she was chatty and amiable, urging me to call her “Katya.” I challenged the bit about “literally pressing her nose against the glass” when the wrought iron would have prevented any such maneuver. But she stuck to her version, claiming the bright lights allowed her to see the statue for what it was—the real deal.

My editor, Eric Gibson, who is now editor of the arts in review section of The Wall Street Journal, and I talked with others in the field. Some said they couldn’t judge on the basis of a photograph; others were emphatic in their dismissal. “It is absolutely impossible, and for a thousand reasons, that this statue is by Michelangelo,” insisted Paola Barrocchi, a professor at the Scuola Normal, the university in Pisa. Another highly respected scholar, Leo Steinberg, asserted, “[I]ncoherence prevails, along with a sweetish allure that I find foreign to the 20-year-old Michelangelo.”

Many were troubled by the media frenzy kicked up by Brandt’s “discovery.”—her collaboration with the Times before publishing more substantial documentation, her appearances on Charlie Rose and the “News Hour with Jim Lehrer”—and by the Met’s promise to curate a show before seeing all the proof or gaining the cooperation of the French government, which technically owned the sculpture.

I talked also with Jesse Kornbluth, who had pitched a Cupid story about ten years earlier, and had written an updated version that he was shopping around. Jesse was a friend from my earlier lives as an editor and sent it over for scrutiny from my superiors. Perhaps this was the answer to our quest for an ARTnews take on the dilemma. Alas, the piece was filled with gossipy innuendo about Brandt’s past (as I recall, Jesse claimed she was having an affair with the Times critic John Russell—or maybe that was just in conversation with me). ARTnews editor-in-chief, Milton Esterow, and others on staff deemed it too nasty. (Kornbluth sold the story to New York magazine, at a time when much of journalism was not routinely digitized for the web, and he is no longer around to remember our exchanges. So I regret that I can’t revisit his article with him.)

I next spoke with James Beck, Columbia University’s Renaissance expert, who made the very sensible suggestion of visiting the statue in person to weigh its merits. When I invited Katya to join us, she turned hostile. “Ms. Landi, you are making a circus out of a very serious issue of scholarship.” I responded, “I think you’re doing a pretty good job of that on your own.”

And so off to the French cultural embassy I went with Professor Beck and his colleague Michael Hall, a dealer and collector of Renaissance art. As we circled under the watchful eye of a guard, Beck and Hall said they were troubled by the figure’s proportions—“the large head, large neck, and skinny body.” Beck cited Leon Battista Alberti, “the main theoretician of the Renaissance, [who] says that when the head is very large and the chest is small, that would be very ugly to see.”

The Met’s James Draper said in a phone interview that he had much the same reaction initially, but that “the whole composition isn’t around to defend itself.” Bertoldo, he said, also favored large heads and long legs.

Beck found the Cupid’s hair to be problematic. “This is kind of an impressionistic way of making hair. To me, even the hair of the David, which is very intellectualized, grows out of the head. It’s not applied to head.”

The statue’s quiver, made from a lion’s paw, according to Brandt in a separate conversation, was “just the sort of ingenious touch we would expect from the young Michelangelo.” And the rough cross-hatching on its surface, claimed Brandt, matched the kind of detailing in other works by the sculptor. “It’s hair, not cross-hatching,” scoffed Hall. “The lion’s paw is the skin of an animal, so these are the tufts on the back of it.”

And so it went, around and around, with Beck claiming the lack of anatomical detail on the stomach and buttocks to be very unlike Michelangelo. “The form of the buttocks is just not articulated at all. I find that terribly amateurish.” Hall volunteered a definitive attribution: “It’s close to Niccoló Tribolo. He was one of Michelangelo’s followers, and was interested in more decorative kinds of sculpture.” Beck said the figure couldn’t be dated before 1540, when the sculptor would have been 65 years old. Draper, who also declined to join us in our tour around the statue, placed the Cupid between 1492 and 1494, roughly contemporaneous with the The Battle of Lapiths and Centaurs in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence.

In an essay that accompanied our report on ARTnews, the eloquent and hugely respected scholar Leo Steinberg gave his judgment, supported by a dissection of the figure’s anatomy, like “the puny chest slightly atwist on an overlong pelvis” and “the boy’s neck inflated to three times the girth of the upper arm at the shoulder” and “the right cheek planed down like carved masonry.”

Nevertheless, Brandt went on to present her thesis in the Burlington Magazine, and Beck published a lengthy rejoinder in Artibus et Historiae in 1998. In the years since Brandt made her pronouncement, the statue has been the centerpiece of an exhibition at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence and featured alone at the Louvre in Paris, where a dissenting curator, Jean-René Gaborit, labeled it an anonymous work of the later 16th century.

When I re-reported the story in 2009, William Wallace, the Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History at Washington University in Saint Louis, said, “This was probably one of the most popular fabrications ever published. We’ve been urged to accept all kinds of secondary and circumstantial evidence to convince us, when in the world of connoisseurship it’s the object itself that should be first and foremost to convince. And the object itself is not totally and thoroughly convincing.”

Now the boy is on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, on a ten-year loan from the French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, and is firmly attributed to Michelangelo. In 2019, when its loan to the Met was renewed, director Max Hollein gushed, “Michelangelo’s youthful genius is apparent in his exquisitely rendered Cupid. The work emits an emotional and intellectual charge, and it is an honor to present this stunning sculpture to our millions of visitors.”

If you’re in New York, go see it for yourself in gallery 503 at the Met. I would love to hear your opinion.

p.s. I’ve been following with pleasure another Substacker, who calls herself the Rogue Art Historian, and presents regular lively discussions about art and artists. Check it out here and sign up for free.

A wonderful read, Ann, and a truly great bit of reporting. Thank you. I remember when this whole thing hit the Times and I was so excited. Stupid me. Later, when I heard more about it, I felt manipulated and deceived. So similar to so many things in the news...

In any event, I deeply admired scholarly connoisseurship until I read a book about Bernard Berenson and learned how much ego, politics, and money got in the way of judging. Not merely because one ends up with scholars battling one another, as in the case of this Cupid (like you, I find it doesn't match what I think of as Michelangelo, but I admit to knowing far less than even you modestly claim to know), but because the whole matter of according attribution by style rests on a bed of subjectivity.

Remember the Rembrandt project, where a group of scholars de-attributed an enormous number of Rembrandt paintings? Museums all over the world had to redo their labels to say "School of Rembrandt," or "Attributed to Rembrandt." Later, a good number if not most of these ostracized Rembrandts were reattributed to him. What caused the mess I don't really know.

It's strange to think that if any of us were told this Cupid is definitely, without question, a work by Michelangelo, we'd look at it differently if we're told it's by some B-list artist. Now that the poor thing has been verbally torn to shreds by a gazillion judges, for me to find in it whatever bit of aesthetic virtue it might have is impossible.

A great summary of the pitfalls of "scholarship" and the desire to make an object belong to a big name!