They Cried. They Gasped. But No One Fainted.

No, this is not about a Trump rally. But strong reactions to works of art.

There are a number of ways to respond to art, ranging from confusion and boredom to Sister Wendy-like rapture. Last week, Artnet writer Ben Davis added a new emotion to the spectrum, one I’d never thought about. He calls the reaction “aesthetic chills” and elaborates: “the moment when, experiencing a work of art, you feel a rush of physical emotion, a shiver that runs down your spine.” He cited Janet Cardiff and George-Bures-Miller’s installation Forty Part Motet (2001), a choice I would second, having seen it when it debuted (and soon thereafter profiled the artists for ARTnews). In this installation, 40 standing speakers arranged in a circle play a choral arrangement by Thomas Tallis (1505-1585), and somehow the combination of music and speakers standing like scarecrow sentinels proves a true spine tingler.

To the chills category, I would add Gary Hill’s Tall Ships (1992), which I saw only once in Seattle in the late 1990s, but it’s stayed with me all these years. It’s a video piece in a separate gallery in which “figures, standing or seated and ranging from one to two feet high, first appear in the distance, at about eye level,” says Hill’s website. “As the viewer(s) walk through the space, electronic switches are activated and the figures approach the viewer until they reach approximately life-size. They remain in the foreground, slightly wavering, until the viewer(s) leave the immediate area.” It was profoundly unsettling, somehow evoking a shivery sense of one’s fragile mortality, perhaps because it was like an encounter with the souls of the dead.

Not to parse emotions too finely, but Davis’s ruminations reminded me of a post from Vasari21 in 2017 documenting other writers’ strong reactions to works of art.

Neither I nor anyone I know has ever suffered the peculiar aesthetic shocks known as Stendhal Syndrome, named after the great 19th-century French novelist and described in a journal called The Florentine as “a psychosomatic illness that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, confusion, and even hallucinations when the individual is exposed to an overdose of beautiful art, paintings, and artistic masterpieces.”

Nonetheless I was curious to ask critic friends and acquaintances what kind of emotional and/or visceral reactions they’d had to works of art, ongoing or in the past. And so here’s an intriguing round-up. (I’ve included the late Arden Reed, a scholar who left us far too soon and whose book Slow Art is a fascinating study in the art of seeing.)

Christopher Knight (art critic for The Los Angeles Times): Only once have I wept in the presence of a work of art — I mean actual tears welling up—and that was in the early 1980s at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, while looking at Giotto’s famous frescoes. The response was slow, not sudden. I think it came from realizing that everything I thought I knew about art could not account for how moving they are. The sense of loss was profound—liberating, too.

Karen Wilkin (art critic for The Wall Street Journal, The New Criterion, and other publications): On occasion, confronted by a particular work of art I’ve had an incredibly strong, unexpected, and unpredictable response. It can be from any period, a painting, a sculpture, a work on paper, a building, sometimes a video. It can be a work I’ve never encountered before or one I thought I knew well. I’ll spend what seems to be a reasonable length of time looking and then, when I try to turn away, the work grabs me by the shoulder and tells me that I’m not finished yet, that I haven’t fully grasped everything there is to be considered. It can happen several times in a row. Matisse has done this to me often. So has Titian. I’ve been stopped in my tracks by a12th century sculpture by Gislebertus from Saint-Lazaire in Autun and several of Anthony Caro’s last steel pieces. I spent three hours watching an entire Douglas Gordon video of a burning piano. (The guard kept giving me concerned looks.) I kept trying to leave, thinking I’d “gotten” the piece, but I couldn’t. It’s most exciting when this reaction is triggered by something completely new to me and/or puzzling. I suppose this is reverse Stendhal Syndrome; instead of needing to flee, because of sensory overload, I crave more and more, in spite of myself.

David Rubin (curator, artist, and critic in Los Angeles): Two memorable experiences and one recent one come to mind. When I saw my first small Rothko painting upon entering graduate school at the Fogg Art Museum in 1972, I was dumbstruck. My response to the optical effects of light emanating from the painting evoked in me a feeling that was transcendent and ethereal. Almost a decade later, when I stood in front of a Wallace Berman “Verifax” collage for the first time, my mind went to another place and then came back. The presence of so many powerfully symbolic images in one grid, presented like X-rays, left me speechless…until a few minutes later when I thought to myself, “This is our universe, these are our options.” Last week, I had the pleasure of walking through the John McLaughlin retrospective at LACMA. There were multiple moments when I was stopped dead in my tracks. Through impeccable craftsmanship and compositional choices, which were particularly daring in terms of color juxtapositions, McClaughlin made me feel what Barnett Newman (who also mastered how to do this) called the sublime. In all these instances, I believe the artists appealed to something that is universal….call it heightened consciousness, being at one with the universe, or simply enlightenment, it takes a great artist to get us there.

Arden Reed: After years of repeated encounters with them, certain paintings continue to thrill me, to make various chakras hum, to provoke visceral if not synesthetic responses. Three examples:

A gray Agnes Martin whose name I forget. Because it’s the large, six-by-six-foot format, it fills your visual field; you relate with your body along with your eyes. Over a lightly penciled rectangular grid, delicate veils of the thinnest color seem to drift. They’re never quite where they were when last you looked. However material, the canvas provokes out of body sensations, indeed, out of this world, or “Ariel” sensations. I feel groundless yet serene.

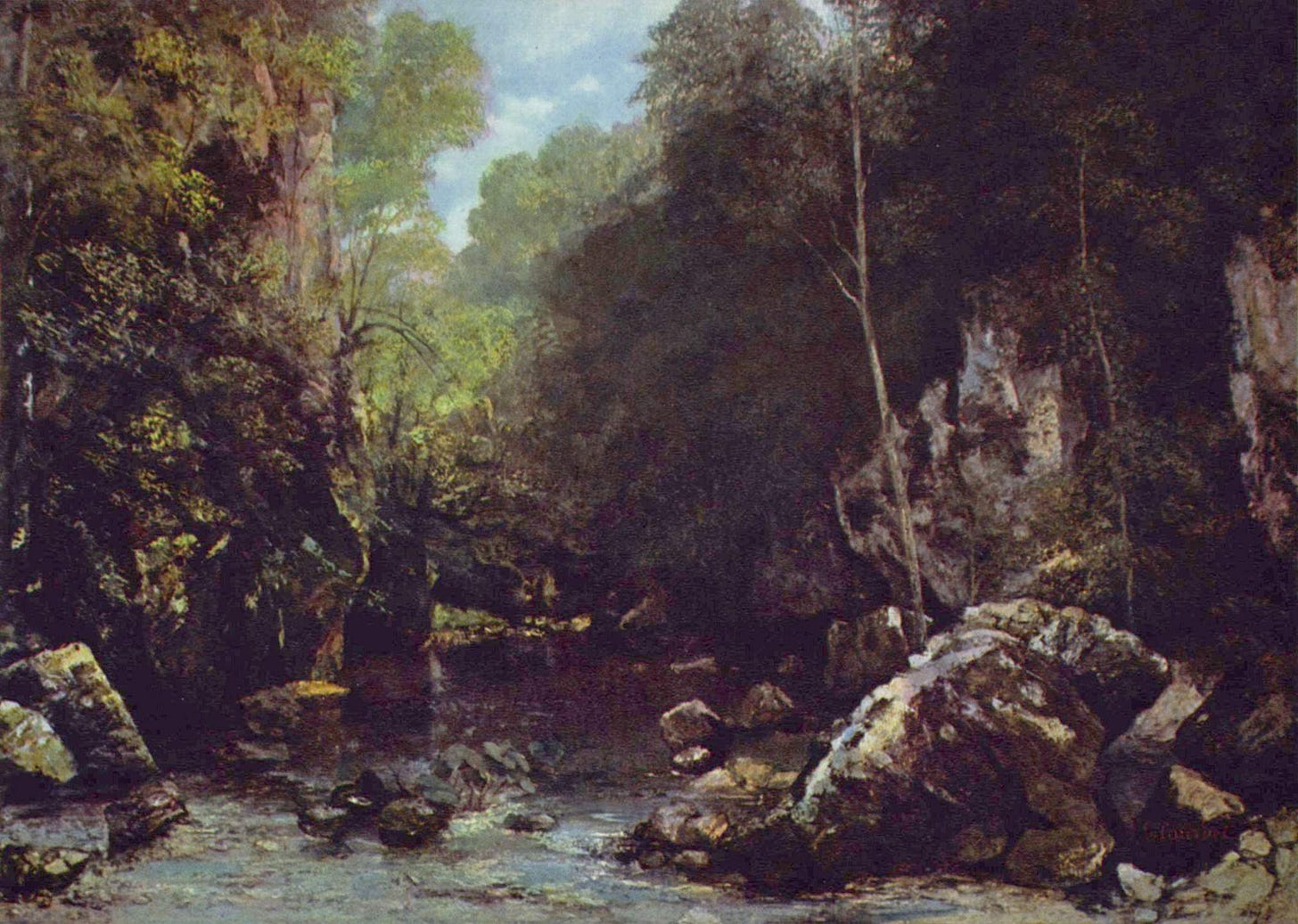

Caliban comes to mind when I look at the Norton Simon Museum’s Stream of the Puits-Noir at Ornans (1867-68), a landscape by Gustave Courbet. Is it late fall or early spring? Dawn or dusk? In any case, my eye wants to follow the stream back into the recess between two massive granite cliffs. The overarching branches both invite and resist penetration. I hear the stream rustling as it spreads from back left and eventually spills out over the front edge of the canvas. And so the painting situates me in the stream, and my feet feel damp and chilled.

Between sky and earth, I locate an early Matisse in the Phillips Collection: Studio, Quai Saint Michel (1916). Curtains part, inviting us into a classic Parisian garret, circa 1910, where I smell fresh paint on a canvas next to the empty chair. The artist has just sketched the contours of a nude, reclining on a sofa covered with a red cloth. I hear him asking her to remain just so—he’s got the pose he wants. If I looked out the tall windows behind the chair, I’d see some steps descending to the Seine, a tower of the Conciergerie, a spire of the Sainte Chapelle, and from upriver I would hear the bells of Notre Dame chiming.

For me it is particular exhibits, the Phillips Collection Rothko room which I saw as a student in the late 60s was an early emotional experience. The Doris Salcedo exhibit at the ICA Boston was by far the most emotional experience ever. Especially the shoes. I also cried watching The Visitors by Ragnar Kjartansson at the ICA.

Great piece. Setting me thinking about the works of art that have evoked similar feelings in me. Will circle back with a short list.