With Oscars season over and done with and Meghan Sussex sprinkling flowers on everything in sight and the powers that be in DC taking a sledgehammer to democracy as we know it, I believe it is time for some new distractions. So this week I am suggesting a handful of my favorite documentaries about artists.

What makes for a good movie about an artist? Many I’ve seen bring a hushed and naïve reverence to their subjects, producing a narrative as solemn and self-important as a PBS special—or a golf game. Others short-change the art to tell a story (and the other way around). In recent years, artist documentaries seem to be getting more and more sophisticated—injecting animation, using professional actors to provide narration, and offering smart camerawork to rival that of a feature film.

By “films about artists” or “artist documentaries,” I mean nonfiction narratives, not the Hollywood fabrications that tell the stories of Michelangelo, van Gogh, Frida Kahlo, or even Jean-Michel Basquiat. There are some terrific fictional takes out there (including at least six about Vincent), but for now I’m limiting the field to those that aspire to tell the whole truth and nothing but.

Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress, and the Tangerine

2008; written and directed by Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach; running time, 99 minutes

Fans of Louise Bourgeois, who in 1982 at the age of 71 became the first woman honored with a major retrospective at MoMA, are probably familiar with the psychological underpinnings of her art. Her father’s open liaison with the girl’s nanny, the “mistress” of the title, caused the artist enormous distress as a child—as did the tension between mother and father—and gave rise to a body of work that stems from a direct pipeline to the unconscious. As one of her sons notes in the film, there was “no separation between art and life.” But her history is revealed in a slow and indirect fashion, and it is not till about a third of the way through that Wallach, who also did an admirable job bringing Emilia and Ilya Kabokov to the screen (see below), gets to the heart of Bourgeois’ thorny trajectory.

We are first treated to a number of stunning shots of installations, but the story behind them doesn’t begin to gel until Bourgeois talks about how her father came back from World War I and commenced to some serous womanizing. Her development as an artist is not completely clear, though there are allusions to a meeting with Brancusi in 1953 and her marriage to art historian Robert Goldwater, who was a far bigger presence on the New York art scene in the 1950s.

But stick with this film for a fine overview of the artist’s work, which was masterful in almost any medium—from bronze and marble to haunting installations to crudely stitched fabric sculptures. What you will read between the frames is stunning in its immediacy: her close relationship with her devoted assistant, Jerry Goruvy; her almost self-mocking impatience and petulance in late life; and her breakdown, on camera, as she reminisces about the savage way her father taught her to peel a tangerine. The final sequence of images, of the many Bourgeois “Spiders” around the world, unfolding as Laurie Anderson sings from “O Superman,” is alone worth tracking this one down. Available for free on YouTube.

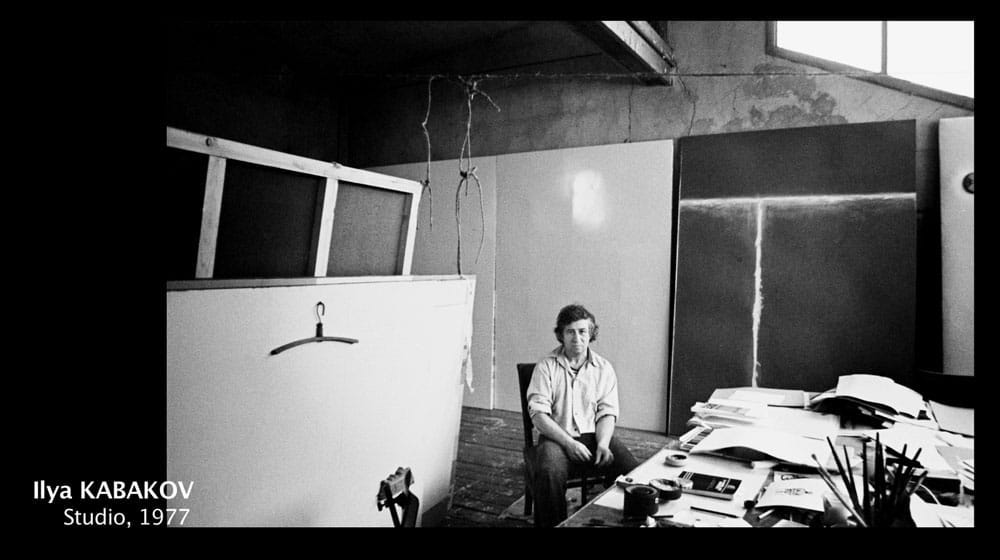

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Enter Here

2013; director, Amei Wallach; running time, 1 hour, 43 minutes.

An engrossing and multi-layered portrait of the Kabakovs—primarily Ilya—whose six-decade career resulted in some 600 exhibitions and 400 installations after he left Russia in the 1980s and before his death in 2023. The film’s occasion was the triumphant return of the Kabakovs to Moscow’s mammoth art space known as the Garage (one of six exhibitions that ultimately opened at different sites), but the film strikes a balance between the art and the life, including enough history to understand the enormous and generally devastating changes in Russian life over the last century.

Kabakov and his mother fled to Samarkand, in Central Asia, when the artist was seven. The boy’s sketches, made on the sly, were good enough to get him into the Leningrad Academy of Art, which had also relocated to the hinterlands. He later transferred to school in Moscow, watched over by his mother, who was reduced to sleeping in public toilets and camping out in the houses of friends. Later, when she was in her 80s, Ilya asked her to write down her life story, and these became the basis of some of his most moving installations—and some of the most wrenching moments in the film.

After the death of Stalin, under Kruschev, as Ilya explains, there were “no shows, no galleries, the only life was in the studios.” Artists illustrated children’s books in order to survive, but in 1971 Ilya produced the first conceptual projects in the Soviet Union, appropriately in an underground café. By the time he arrived in the West in the 1987, living in various European countries for several years, it was with a sense that someone was always controlling his life: “a mysterious eye watched you all the time.”

The film is generous in showing the Kabakovs’ installations (and how the Moscow projects evolved), which don’t require a lot of back story to gauge their impact. Threaded throughout are intimate glimpses into Soviet life across many decades of idealism and disappointment. The Kabakovs come across as collaborators—he makes the art, she does the negotiating and problem solving. One would like to know more about how they met and how they work together, but it’s a minor quibble in an otherwise engrossing portrait of a great artist. Also on YouTube for free.

Alice Neel

2007, written and directed by Andrew Neel; running time, 82 minutes

Alice Neel, now widely recognized as one of the most arresting portraitists of the 20th century, is another female artist who didn’t begin to receive her due till late in life. This documentary, made by her grandson, has an odd, disjointed quality, but that is in itself compelling and accounts for a certain grainy and intimate vitality, like leafing through someone’s album of old family snapshots.

Neel’s life was fraught with tragedy and plain damn bad luck. She married a Cuban charmer named Carlos Enriquez and moved to Havana as a young woman. Her first child died of diphtheria, and her early canvases focused on loss and abandonment and reflected her Depression-era milieu. Other doomed relationships produced three more children, and as the art world evolved in the 1950s—turning its attention to Abstract Expressionism—Neel was isolated in Spanish Harlem, living on Welfare.

But painting was what she loved to do best. “It’s a privilege to paint,” she notes. The deeply felt quality of her portraits, awkward but also inexplicably revealing (check out her likeness of a wounded Andy Warhol) is made clear when she confesses that after her subjects leave, “going back to myself is difficult.” The tangled relationships with her children, one of whom seems to have been a suicide (it’s not entirely clear from the narrative) are captured through archival footage and interviews (at one point, the director argues with his father and the debate becomes so heated that he switches off the camera).

By the 1960s, the counterculture began to embrace the artist and her work, and there is a lovely sense of triumph in her later life, when she finally enjoys a retrospective at the Whitney. In her 80th year, Neel bravely painted a self-portrait that is much like this film: searching, unapologetic, and raw. Available on Amazon.

2012; director, Alison Klayman; running time, 1 hour and 31 minutes

Artist-activist Ai Weiwei was in the news again just last month when he was deported from Switzerland for complicated reasons surrounding his visa. For virtually the entirety of his career, the outspoken and controversial Chinese-born artist has been in the headlines more than most in avant-garde circles, and the young American filmmaker Alison Klayman first caught up with Ai for a feature-length film right after the horrific Sichuan earthquake killed 70,000 people. Ai began posting photographs of the victims on his blog, writing about “the tens of thousands of lives ruined because of …. blood sellers in Henan, because of industrial accidents in Guangdong and because of the death penalty. These are the figures that really tell the tale of our era.”

The then 24-year-old Klayman, working largely by herself, documented Ai’s brutal clubbing by the police, his crusade against the shoddy construction in Sichuan, and the raid on his studio that ended with the artist’s disappearance for three months. His background as the son of a noted revolutionary poet who fell out with Mao and was banished to the provinces is woven into the story, as are—briefly—his 12 years in New York, where he got his start as a street portraitist and learned to speak excellent English.

There is a lighter side to this larger-than-life figure, as when he plays with his toddler son (by a woman other than his wife), declaring that fatherhood “is a treasure,” or chows down on pig trotters in Sichuan and corned-beef at the Carnegie Deli in New York. Not much attention is paid to the art—what it is or how it’s made—but when he dumps millions of hand-painted ceramic sunflower seeds on the floor of London’s Tate Modern, it’s an impressive sight, a breathtaking statement about individuality lost in collective identity. Available for free on YouTube. (And for a full look at Ai’s activities, past and present, check out this site.)

Frida

2024; directed by Carla Gutierrez; running time, 1 hour, 27 minutes

Given the impressive number of museum shows, docuseries, books, and one star-studded Hollywood homage to the Mexican spitfire surrealist, one has to wonder: Do we really need more? Probably not, but this 2024 film packs a lot of sizzle into 87 minutes and tells the story almost exclusively through Kahlo’s diaries and letters, as well as the words of friends and lovers, including two-time (and two-timing) husband, Diego Rivera (the actors who voice these characters are all terrifically convincing).

From the bus accident that destroyed her spine as a teenager to her final triumphant retrospective shortly before her death, Kahlo seldom let her injuries slow her down. She fell in love with Rivera and traveled with him to Detroit and New York, where she was largely dismissed as colorful eye candy; joined the Communist party and had an affair with Leon Trotsky; suffered a miscarriage that helped her find her own voice as a painter; and took up with André Breton, the godfather of the Surrealist movement, who provided a humiliating introduction to cutting-edge art in Paris. And always there is pain, excruciating physical suffering that she transmuted into unforgettable tableaux (my favorite is The Wounded Deer from 1946, shown above).

Above all, it is Frida’s own no-bullshit voice that gives this documentary its most compelling edge. There’s an appealing frankness to her discussions about sex and sexuality, as well as her lifelong infatuation with Diego, a walking heart attack about two decades her senior and five times her bulk.

The only real annoyance in this film—and it’s a big one—is the cartoony tinkering with the paintings, so that we get Frida with chattering monkeys, creeping vegetation, and dripping blood. Her work doesn’t deserve this kind of disrespect. Frida would be outraged. (Available on Amazon)

I realize there are many more recent offerings to stream, and I will get to them soon. If you have favorites, please let me know about them.

Thanks, Anne❤️. As always, informative and insightful. I look forward to watching these. Thank you for feeding my head. 🤗

Okay, I'll check the offerings. thank you