‘Tis the season to head off to the beach (or fling yourself in a hammock) with a deliciously escapist read that will take your mind off our precipitous slide into the insanely nasty dictatorship Donald J. Trump hastens to impose on our struggling republic. (Can you believe Alligator Alcatraz? Am I dreaming this?)

Sometimes you simply have to take a break from the news or you will lose what’s left of your wits.

I am always on the lookout for good novels with an art-world theme or rousing retellings of art history. But of late I’ve been extremely disappointed in the samples of several books I’ve downloaded (Scrap, Gabrielle, The Californians, Anita de Monte Laughs Last) because something failed to grab me—most often the story or the language simply did not gain a foothold on my imagination. (I might add that books these days often seem so sloppily edited that I’m aghast at the dreary sentences and mangled metaphors that slip past editorial eyes—and I’m gathering that good copy editors, those staunch guardians of grammar and readability, are simply a thing of the past.)

So I’m recycling several of the books I’ve loved from years past, and including only one new title, Sebastian Smee’s riveting Paris in Ruins. Just because a book is a few years old doesn’t mean it’s lost its luster. I recommend titles because they dwell in the mind long after you’ve closed their covers (or darkened your device).

Happy reading!

Paris in Ruins: Love, War, and the Birth of Impressionism, Sebastian Smee (Norton). A Pulitzer-prize-winning critic for The Washington Post, Smee brings a novelist’s eye to this deeply researched account of what Victor Hugo called “The Terrible Year” of 1870-71 when France picked a ruinous war with Prussia, deposed its emperor (Napoleon’s nephew), saw its capital city besieged by German troops and, after an ignominious surrender, spiraled downward into civil war, with the radical Commune fighting a losing battle. At the heart of the book is the difficult but passionate romance between Edouard Manet and Berthe Morisot, probably never consummated but nonetheless of momentous importance for both painters.

While other artists in their circle of future Impressionists fled the incessant bloodletting — Pissarro and Monet to England, Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet to England, Paul Cézanne to a hiding place in a village near Marseille — only Manet, Morisot, and their close friend Edgar Degas “had the misfortune of being trapped in Paris during its long winter siege,” writes Smee.

The sheer accumulation of anecdotal detail is enough to keep the pages turning. Manet and Degas engaging in target practice in anticipation of the Prussian advance; Parisians reduced to eating rats and the animals in the zoo (nonetheless prepared by a famed French chef); the perilous balloon ride arranged by the pioneering photographer Nadar to deliver mail beyond the Prussian lines. And who knew that carrier pigeons could prove adept at delivering secret messages from Paris to the hinterlands?

As the world around us turns ever more savage, it’s good to be reminded that Western nations hav suffered far worse.

Ninth Women, Mary Gabriel (Little, Brown) The Abstract Expressionist generation has gone down in history as mostly male and exceedingly macho. Jackson Pollock boozing it up and brawling at the Cedar Bar. Willem de Kooning slashing his way through that still-disturbing “Woman” series. Franz Kline bravely paring back his imagery to a few bold black strokes. Museum shows, biographies and tomes on modern art still celebrate those pioneers of a distinctly American movement, launched in the 1940s and in full flower by the middle of the next decade.

And yet there was a significant cohort of women painters who came into their own at the same time and were by and large accepted as equals in the scruffy downtown milieu that nurtured them all. Surveys at the Denver Art Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have paid homage to their accomplishments, and now comes Mary Gabriel’s sweeping and delightfully readable Ninth Street Women. Gabriel, the biographer of characters as diverse as the suffragette Victoria Woodhull and pop superstar Madonna, focuses on five painters: Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan and Helen Frankenthaler. These artists are material enough for 700-plus pages, but the author also weaves a vivid tapestry of bohemian life in New York as that city was supplanting Paris as the capital of the art world. (You can read my full review here.)

Sally Mann: Hold Still (Little, Brown). Some may remember the huge controversy that attended the publication of Sally Mann’s photographs of her three children, in a collection called “Immediate Family,” in the early 1990s. In the photos themselves, of the kids naked and often striking make-believe adult poses, and in the profile presented in The New York Times Magazine, Mann came off as imperious and a bad mother, willing to sacrifice her children to her art. The reaction was swift and outraged: reams of letters to the editors, harsh assessments by critics, and assaults on the family, including at least one person who harassed them for years.

Two decades later, the photographer coolly assesses the reaction and her own response, but this book is far more than a photographer’s memoir of her subjects. Mann is a stylish and commanding writer who has sifted through a trove of family papers and old photos to excavate a Southern past more gothic than any imagined by Carson McCullers or William Faulkner. Generously illustrated, this is a story of troubled but gifted parents, memorable ancestors, long-suffering family retainers, clandestine affairs, and murder and suicide.

Most bracing of all is the way the artist writes about her vocation and what drives her. “Art is seldom the result of true genius,” she writes, “rather it is the product of hard work and skills learned and tenaciously practiced by regular people. In my case, I practice my skills despite repeated failures and self-doubt so profound it can masquerade outwardly as conceit. It’s not heroic in any way….I make bad picture after bad picture week after week until the relief comes: the good new picture that offers benediction.”

Self-Portrait with Boy, Rachel Lyon (Scribner)

An ambitious young photographer, living in near-squalor in a DUMBO loft in 1991, just happens to catch a neighbor’s young son as he falls to his death outside her window. Lu Rile knows it is the sort of image that can launch a career (provided you sustain disbelief long enough to accept that one photo is capable of such a thing) but must struggle with three menial jobs, an ailing father, a skeptical dealer, and her budding friendship bordering on infatuation with the boy’s grief-crazed mother.

Lyon’s remarkable debut novel Is part ghost story, part romance, and as one reviewer put it, “an unforgettable portrait of a true art monster—a young woman hell-bent on pursuing greatness, no matter the cost.” What sets the book apart from other novels that attempt to portray the art world of any era is Lyon’s refusal to indulge in the usual stereotypes by creating sharply etched characters in crackling, charged language. She also gets the nascent real-estate boom closing in on an artists’ enclave, and the fear and greed urban development can unleash in a fragile community.

And, of course, the ruthless ferocity of many young artists, for whom every event, no matter how grotesque, is a potential subject. Consider her description of Lu’s finding a nest of rats in her loft:

“They were babies, each not even the size of my fist, pink with sightless eyes and squirming feet. They were curled together in a pile of rags and torn photo paper and shredded cardboard. The mother was squeaking shrilly, concealed somewhere behind me. I rose up again and left the darkroom to retrieve my Rolleiflex. I came back in and squatted down and focused in on their tiny groping hands and open mouths. The mother was going out of her mind, squeaking wildly as if she were a much larger beast, hunkered down and ready to attack. I took a picture, then got up and left her to her brood.”

Self-Portrait with Boy is so ably constructed, so memorable and haunting, that I closed its covers for the first time and then read it all over again.

Please let me know if you’ve got a book you’d like to share!

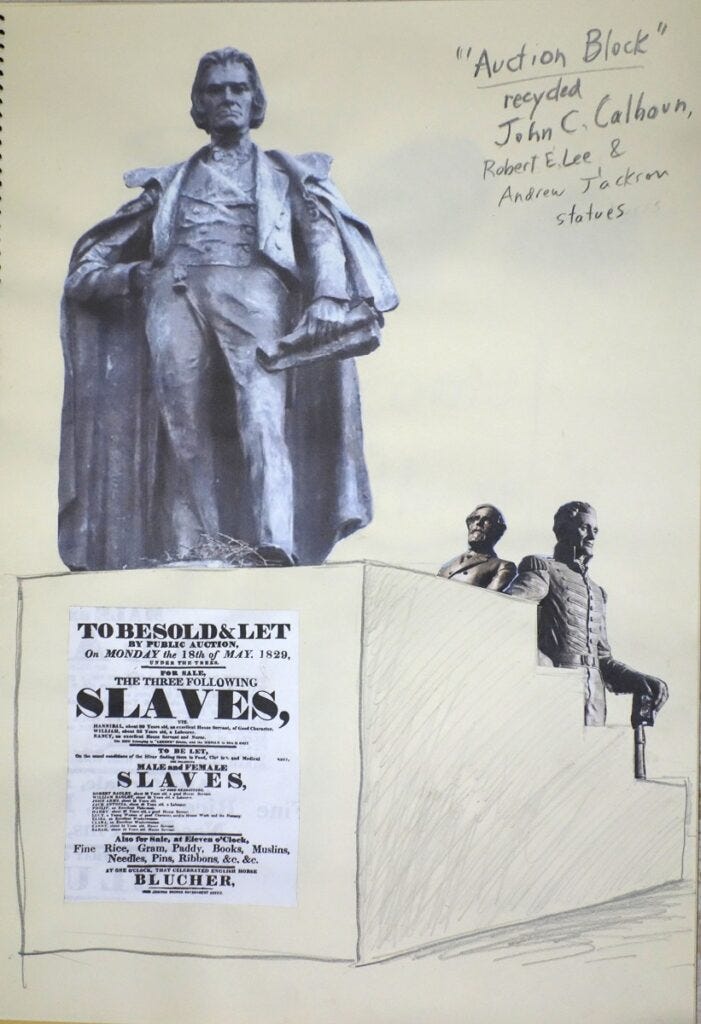

The Design-a-Heroic-Monument Contest: As you may or may not know, page 820 of Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” includes $40 million “for the procurement of statues” for the National Garden of American Heroes. “The national sculpture garden is one of the president’s central priorities for the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence next year, and will feature life-size statues of 250 great individuals from America’s past who have contributed to our cultural, scientific, economic, and political heritage,” according to ARTNews. The garden is intended to “create a public space where Americans can gather to learn about and honor American heroes,” according to a press release from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Selected artists will receive awards of up to $200,000 per statue, which must be made of marble, granite, bronze, copper, or brass. The New York Times previously reported that President Trump “directed that subjects be depicted in a ‘realistic’ manner, with no modernist or abstract designs allowed.”

But, you know what? To hell with all that! The challenge for readers is to come up with a design for a monument dedicated to the hero/heroine of your choice. I can’t give you 200 grand, but I will assure you ample space to let your imagination roam far and wide. Just send me a sketch and a bit of a blurb to describe your project.

If you need some inspiration, check out Parts One and Two of our monuments contest from five years ago.

Please send sketches, plans, jpgs, etc. to ajlandi33@gmail.com by August 8, 2025.

Mary Gabriel's Ninth Street Women was an engaging and very well written book.

We have few classic journalists left in the U.S. AI ????

I love your new contest....Cheers!

Ann, since you are including older books, Donna Tartt’s “The Goldfinch” is my desert island art novel.